You are reading the archive for the category: Fencing

Filed as Classical Fencing, Fencing, Historical Fencing with no replies

It is my distinct pleasure to announce to the community that Dr. Ken Mondschein has been chosen as one of the USFCA’s first historical fencing masters. It is my opinion that Ken has worked his entire life to become the person who could fulfill this need in our community.

Maitre d’Armes Historique

- Maestro Mondschein holds a PhD in medieval history and is a Fulbright scholar which places him within the ranks of the scholastic elite.

- He is a classically trained fencer with a ready knowledge of western fighting theory. In this field, he has taken multiple public examinations from an accrediting fencing body which provides him knowledge and experience necessary to examine instructors.

- He is one of the most prolific modern authors for historical martial arts including two translations of primary sources. These works are enriched both by his academic expertise but also grounded in his classical tradition. This combination provides a modern reader with immediate access to the historical material.

- His knowledge is broad. Maestro Mondschein is equally at home in full harness on horseback as he is on the classical strip. With academic and applied knowledge both broad and deep he embodies a Carrancine spirit of excellence within our community.

It is my opinion that through some miracle of blind luck, the USFCA chose perhaps the most qualified master to begin their program for historical instructor certification. I personally had reservations about the USFCA’s historical instructor certification program but at his core Ken is one of us and he understands what this community is about. No process for certification will be perfect but it gives me a great deal of reassurance to know that he is part of this project. When I think on my concerns, each one is addressed by, “Ken, will fix this.”

My congratulations to Maestro Mondschein for he well deserves this. Likewise my congratulations to the USFCA; I don’t think they yet fully realize the potential of the master they have chosen to start their program but I heartily approve. I don’t expect the USFCA to be the only program to certify instructors but I expect it will be a good one with Maestro Mondschein doing the work.

Master at Arms, Puck Curtis

Filed as Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with no replies

What is an Atajo? To understand the Atajo it is useful to understand the primary causes that make it work.

I’m intentionally going to present this from the perspective of a Pachequista (a follower of don Luis Pacheco). Pacheco literally defined the fencing master’s examination in Spain so in this regard his work is “canonical”.

The Advantage of Downward Pressure

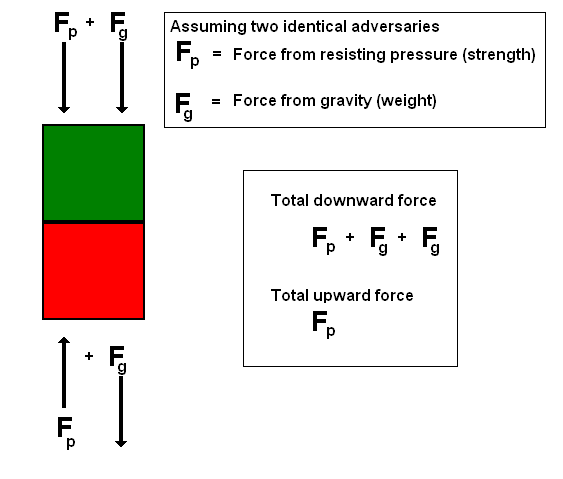

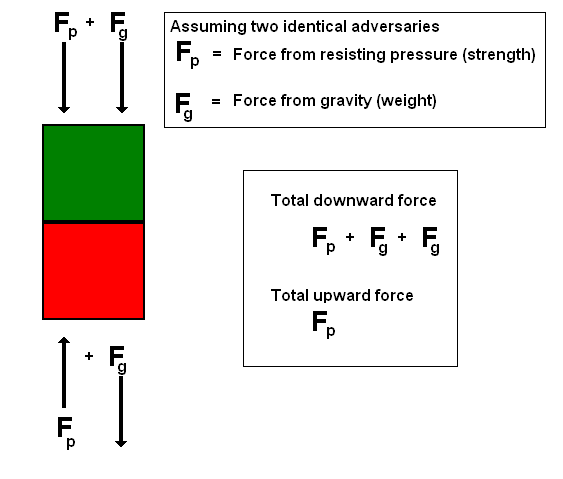

If I extend my arm out toward you with the palm up and you press down while I resist you will probably be able to lower my arm. The Spanish call this the superior nature of the natural movement (descending) versus the violent movement (rising). Your own body also provides an advantage when you use your shoulder and body to assist in the motion to increase the downward force.

Principle: If all other factors are equal a downward force will defeat an upwards resistance.

When two equal adversaries resist each other, gravity lends a hand.

The Advantage of Degrees of Strength

I have already written an article about blade mechanics, but every swordsman worth his or her salt should already know that in contact between two weapons, the swordsman with superior degrees of strength in the engagement has an advantage of power both offensively and defensively.

Principle: When two swords oppose each other in an engagement, the weapon with greater degrees of strength is stronger and has an advantage.

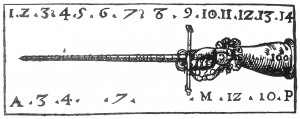

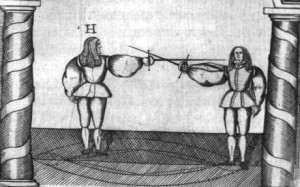

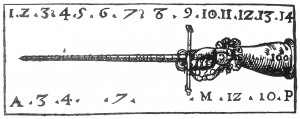

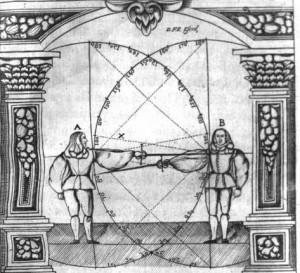

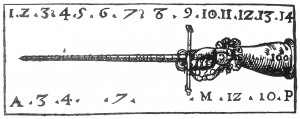

Carranza's degrees of strength showing higher values as stronger.

For more on strength in engagements consider this article:

Spanish Fencing Notation 5 – Strength of the Weapon

The Advantage of Time

When two adversaries act against each other the swordsman who can finish execution sooner has an advantage in time. The Spanish use Movements as a tool for understanding time. When the adversary’s attack requires three movements, he can be defeated by a defense or counteroffense which uses a single movement. In addition an engagement that completely closes a line can limit the adversary’s offensive options to ensure that the time advantage is maintained.

Principle: A defensive action that requires a single movement can defeat an offensive action with more movements.

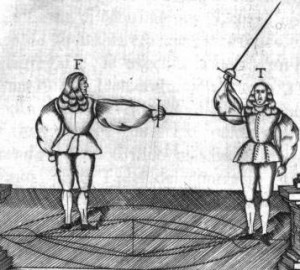

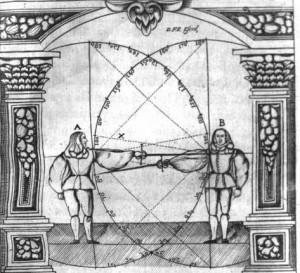

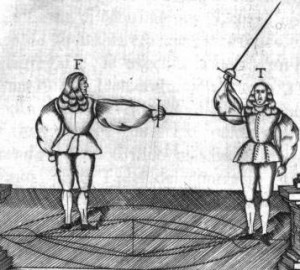

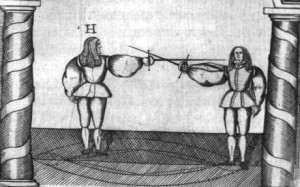

When the adversary attempts to strike with a circular reverse (3 movements) the defender answers with a thrust (1 movement). (Ettenhard Plate 11)

Principle: An engagement which prevents the adversary from attacking in a single motion provides a defensive advantage.

By closing the line, he forces the adversary into a time disadvantage. (Ettenhard Plate 15)

For more on Spanish Movements consider this article:

Spanish Fencing Notation 1 – Vector Notation

Advantage by Domination of the Shortest Path

The Spanish fencer starts with the arm extended and the weapon pointed at the adversary along the most direct path to the target. Knowing that it is easier to push downward then to resist upward, I can use this principle to deny my adversary the shortest path to my body by pushing his blade down. Not only do I increase the distance he must travel to strike my body, I also ensure that my offensive path is shorter and closer to the target.

Principle: By starting with the arm extended along the shortest path to the adversary and then deviating the adversary’s weapon downward you ensure your own path to the target is shorter.

Note: Deviating the opposing steel laterally would be called a desvio or a deflection.

The advantage of the shorter path (Ettenhard Plate 9)

Atajo Defined

The Spanish Atajo unites all of these ideas into a single defensive action which can protect the swordsman while simultaneously providing opportunities and the place from which to strike with safety. Offensively, the atajo can be used to prepare a safe attack that controls the adversary’s weapon. (We would call this preparatory action “dispositive” and the attack “executive“.)

Pacheco in New Science p.365 (1632)

| “Atajo, according to our definition, is when one of the weapons is placed over the other (not in any of its extremes nor with any of its extremes) and with equal or some degree more of strength subjects it and makes it so that the technique that can be formed must be done with more movements and the participation of more angles than those that its simple nature requires.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Pacheco in New Science p.368 (1632)

| “Arriving, then, to the perfect formation of the atajo, it should necessarily consist of three movements: violent, offline lateral and natural. With the first the sword that should subject is placed on a superior plane to the other, with the second it is placed transversal over it, and with the last it subjects it:” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Ettenhard in his Compendium and Foundations… p.154-155 (1675)

| “I am very safely confident that one will have recognized with enough satisfaction that the Atajo causes its effects by means of a superior graduation and of the superior power of the Natural Movement and also that one will concede to me that if it were possible to beat and destroy these two causes, we would see dispelled the end of such superior effects…” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

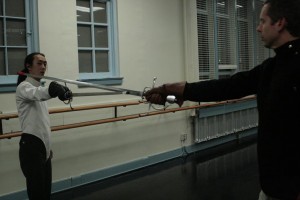

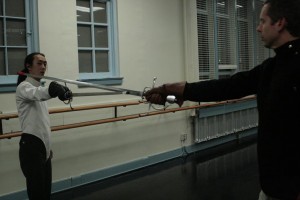

Eric places an Atajo over Kevin's sword. (Click for larger image)

The Defining Elements of Atajo

Between Pacheco and Ettenhard we find these three items essential in placing Atajo:

- Subjection with equal or greater degrees of strength.

- The subjection is placed from above.

- The subjected line is closed so that an adversary cannot strike with a single movement.

When Lorenz de Rada writes later, he adapts the atajo so that you initially seek the subjection from above and if you don’t find it or feel that the adversary is weak in the engagement you immediately spiral towards the opposing steel and closing the opposite line from below. Compare this to the classical transports of 3rd and 4th from high to low or the corresponding half-circular parries from high to low.

Conclusion

This information tells us that Pacheco’s Atajo should start by seeking the superior line with greater degrees of strength in the weapon. The defensive action subjects downward to lengthen the adversary’s path to the target while ensuring your own path is shorter. It might be tempting to equate Atajo with classical engagements but this violates the primary causes of Atajo. Likewise, by definition two swordsmen cannot both have an Atajo simultaneously.

Filed as Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, Historical Fencing with 1 reply

Choose a blade no more than 41.1 inches from cross to tip.

According to the canonical authors, the length of the weapon should be no longer than 5/4 vara. That’s an upper limit just a bit over 41 inches.

Philip II’s Law on Blade Length

What happens when you exceed that limit? You are sent to prison by order of

King Philip II on the first offense and exiled for a year on the second offense.

Philip II

Philip II in 1564 (translated by Mary Curtis):

| That we are informed that in the said cities, villages, and places some swords, verdugos and estocs are carried of more than six and seven and eight palms and from there above in length, from which cause many inconveniences and deaths of men have resulted and continue to result, and wanting to provide a remedy to this, discussed in our council and with us consulted, it was agreed that we should order this our letter to be issued for you for the stated reason, and we considered it as good. Because of this, we order and command that now and from here forward, after fifteen days counted from the day of the publication of this our letter, no one of whatever quality and condition that he might be should dare to carry nor will carry the said swords, verdugos nor estocs of greater than five fourths of vara of blade in length, under penalty that he who carries it falls and incurs for the first time in penalty of ten ducats and ten days in jail and loss of that estoc, verdugo, or sword, and for the second the penalty is doubled and one year of exile from the city, village, or place where he is taken and was neighbor… |

Pacheco de Narváez’s Preference on Blade Length

Pacheco de Narvaez

Later, Luis Pacheco de Narváez directly cites Philip’s law in his books.

Pacheco de Narváez New Science p. 250 (translated by Mary Curtis) tells us this:

| From these and other injuries our King and Lord Philip, Second in name and First in religion and prudence (whose happy memory in these glorious attributes will live in the most extended posterity of men), wanted to free them, justly and compassionately, with paternal love prohibiting under precept and force of law that any of his vassals carry sword, verdugo or estoc, of more blade than five fourths of vara, superior reason he achieved for this establishment, and if it were as justifiable for us to investigate it, as the obligation of obeying it, we would dare to say, that knowing for the organization, symmetry, and composure of the man (leaving the extremes of high and low) that his common stature is two varas in length, like he also has them from the extreme of one hand to the other, the arms open, and that in this all natural is in potential and diffuse action the strength of the parts that constitute him, unless the ones to the others their similar ones, they can communicate what they receive, and that from the left shoulder to the extremity of the right hand there are five fourths, he wanted for universal good that the swords were of this length, knowing that if they exceeded this, it would not be powerful the vigor sent to move them with the suitable quickness; and thus this very wise Prince looked for a proportion so proportionate that one will not find another more proportionate. |

In the seventeenth century, Pacheco de Narváez echoes the sentiments of Philip II in recommending a blade no more than 5/4 varas.

Pacheco de Narvaez’s Opinions on Longer Blades

Knowing that Pacheco de Narváez advocates a blade no longer than 5/4 vara, does he consider it important? If you use a longer weapon against someone using a proper sword, it offends Pacheco de Narváez, and he has some harsh things to say.

Pacehco de Narváez’s New Science p.248-249 (translated by Mary Curtis)

| The affection of our desire will remain offended and with just reason upset if we lose the opportunity of attempting the inconvenient reform of an ancient error introduced in men, about whom without exceeding the limits of modesty one can speak with all contempt, and in others, that all the terms that human courtesy have discovered do not equal its quality and merits. This is the exorbitant excess in the quantity and length of the swords, so much that changing the gender from feminine to masculine, requires it to be called estoc, or with a word of less nobility verdugo, from the problems that are offered, some are related to and offend the reputation and others offer manifest dangers. Firstly, it is known that no one ever spoke with venerable respect nor did the valor remain very esteemed of he who with advantageous weapons attacked his opponent in a forewarned or casual fight. From the fifth generation passes his memory and easy cause provokes, so that in absence or present they give him in the face with the ugliness of this injury. The greatest friend fails to rise in his defense and with honorable respects is ashamed to promote his credit. He who is not a friend speaks with indignity and discourtesy, and the neutral person is inclined toward kindness and compassion for he who suffered with the unequal instrument, without placing the misfortune of the case to the charge of not knowing. If the cause is deduced to judgment, the right makes the guilt worse and with just indignation increases the sentence and punishment, and in taking this into account, competing with time and forgetfulness endures this new word – fraud, disparaging insult with which the people discredit the one who with effeminate spirit does not dare to confront another man without the advantageous disparity that the estoc has in length over the sword. With similar events it comes to mind and renews resentment, and those who deserve praise detest and condemn it again…” |

To summarize, blades longer than 5/4 vara:

- Are offensive, immodest, excessive, and contemptible.

- Will damage your own reputation by decreasing the perception of your valor for 5 generations.

- Cause friends to be too ashamed to speak on your behalf, enemies to disparage you, and neutral parties to favor your adversary.

- In losing, having chosen a longer weapon will cause your guilt to be worsened and the sentence and punishment is increased (judicially speaking).

- Cause you to be viewed as effeminate for not confronting your adversary on equal terms.

- Are regarded by the the people who are praiseworthy as detestable, and they condemn it.

He also goes on about how shorter blades and lighter blades are better for reacting to the adversary and more macho. Practically speaking, the blade should be able to deliver powerful cuts but still be light enough to change direction quickly.

My own opinion is that in an engagement of the weapons, it is useful to be able to cross and uncross your arms as well. To see what I mean carry your sword over your left arm and then grab a friend’s doublet with your left hand. Uncross your arms to bring your point in line with your friend’s chest. This is easier when the blade is shorter and a sidesword fills the role nicely.

Other Authors

Sword from Carranza's Text

The weapon images in the texts of Carranza (1569) and Pacheco de Narváez (1600 – approx. 1630s) show us swords that look different from the long slender rapiers in Thibault. At least in the time period of Carranza and possibly Pacheco de Narváez as well “Spanish rapier” isn’t a precise description of what I would personally consider an edge sword or side sword if you prefer.

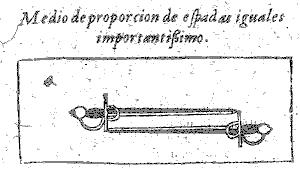

Swords from Pacheco de Narvaez’s Text

Even as late as Francisco Lórenz de Rada’s work in the late 1600s and early 1700s, 5/4 vara is the maximum length. That being said, Girard Thibault‘s work is outside the Spanish canon so if you are interested primarily in Thibault, exceeding 5/4 vara might be acceptable.

Science versus Specific Tradition

Destreza theory is a science which can describe all types of martial arts. The Spanish tradition of swordplay is what is most often described with this science. We must not confuse the science with the specific practice of the art. Pacheco de Narváez and Carranza practice the Spanish tradition, and we can describe this with Destreza fencing theory, but that science is also used as a tool for analyzing Italian fencing and other forms as well.

While Pacheco de Narváez and the other authors recommend a sword of 5/4 vara or less for the martial tradition, Destreza doesn’t recognize a limit on weapon size from the perspective of the science. The montante and other weapons will obviously surpass this value, and Destreza still applies.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with no replies

When a classical instructor from my tradition introduces new techniques each fencing action is taught individually with a focus on form, distance, and timing. Too much emphasis on individual actions can create fencers without depth or the ability to react tactically within the moment.

When a classical instructor from my tradition introduces new techniques each fencing action is taught individually with a focus on form, distance, and timing. Too much emphasis on individual actions can create fencers without depth or the ability to react tactically within the moment.

One of the teaching methods used later in the process is the building of extended phrases of actions to challenge the student. The instructor continually pushes the student with progressively more difficult actions executed in situations more like actual fencing.

By creating an extended sequence, the student is asked to perform at a higher level. Form, Distance, and Timing are still critical and actions executed in extended phrases help to prepare the student for the rigors of the bout.

The 5 Spanish Attacks

- Thrust

- Half Cut

- Half Reverse

- Circular Cut

- Circular Reverse

(For more on the Spanish Attacks read Mary’s Ettenhard Translation )

Our students have been working on these attacks in different situations for the past 9 weeks. At times a focus on technique can feel scripted. While important, technique building work (like repeated lunges in the Italian tradition) may not reflect the action-reaction dynamic that occurs in actual fencing.

By developing a sequence of actions, we provided the students with a glimpse of how a fight could progress and gave some sword-in-hand insight into different choices that could be made in the phrase based on the adversary’s action.

“If he does this, you can respond with this.”

“If he does this instead, consider this response.“

Asking your fencers to consider different tactical options and to think critically about fencing theory in actual practice will create better fencers. Learning to read and adapt to your adversary is one skill that requires attention and practice. There is no substitute in a sword fight for good problem solving skills!

Creating an Extended Phrase

My goal was to include each Spanish attack once during the different mutations of the phrase.

A Guide to My Fencing Notation

Each action is notated once in sentence form as I would call it in a lesson. Then I briefly notate the action again by Movements which is a more Spanish approach. The Spanish notation provides us information about time as well.

Example:

“X. Sentence describing some fencing action…”

- Movement 1 – do this

- Movement 2 – do that

HINT: Count the Movements and you are also counting the tempo. Spanish notation is fairly sophisticated in its ability to simultaneously describe an action and the timing. In Pacheco’s work he often notates an Italian action and then breaks down his tactical responses movement-by-movement. Compare this method to the Bolognese example of notating from starting guard through motion to final guard and you will see a similar idea.

If the notation or jargon looks intimidating, consider peeking at my previous articles to help decode the action.

If there is some interest in this particular phrase, I will do what I can to post a series of videos showing how they can be executed.

The Lesson

Note: All lessons begin and end with a formal salute.

This lesson was performed by pairs of students alternating roles. As the sequence progresses the instructor (the fencer receiving the touch) either invites to initiate the action or responds to the student’s invitation.

Understand the difference between skill-building and fencing

This lesson includes some unrealistic actions. The most heinous example is the initial invitation that removes the point from the line of the diameter. This would be expressly condemned in the Spanish texts because the movement serves no purpose but to create an avenue for the adversary’s attack.

As an instructor, I might use this offline motion as an in-time cue (a motion cue) intended to immediately provoke the student’s attack.

Example: Thrust executed in time

In time as the instructor invites on the outside line, thrust to the chest with a transverse step to the left.

- Movement 1 – Instructor invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Student thrusts with a transverse step left.

As the instructor, I certainly want my student to capitalize on a movement of this kind. In this case, we are using the 1-movement thrust. In the lesson below, I use the 2-movement half reverse instead.

On the student’s side it is perfectly reasonable to assume that at some point during a bout, the adversary might deviate your weapon from the line of the diameter (perhaps with a beat). Knowing how to respond when your point has been deviated from the line is valid training and creating this initial disadvantage provides us with a key training opportunity for placing an atajo over the incoming attack.

I should also point out that the thrust has fewer movements (1) than the other attacks (2-3). In the sequence below, there are numerous instances when a thrust would be a faster response than the various cuts. Again, the intention is to force the student to execute certain technical actions like the cutting attacks and placing an atajo under stress.

Thrust (Line in Cross)

1. From the student’s atajo on the outside line, thrust along the diametric to the chest with a curved step right.

- Movement 1 – Student executes a thrust with a forward movement and a curved step right.

Half Reverse

2. From the instructor’s invitation on the outside line, half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right.

- Movement 1 – Instructor invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Student chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Student delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right.

Half Reverse & Thrust (Line in Cross)

3. From the student’s invitation on the outside line, the instructor executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line followed by a thrust along the diametric to the chest with a curved step right.

- Movement 1 – Student invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Instructor chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Instructor delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line.

- Movement 3 – Student executes a thrust with a forward movement and a curved step right.

Half Reverse & Half Cut

4. From the student’s invitation on the outside line, the instructor executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line followed with a half cut to the inside cheek and a transverse step left.

- Movement 1 – Student invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Instructor chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Instructor delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line.

- Movement 3 – Student executes a half cut with an aligning movement and a transverse step left.

Half Reverse & Circular Cut

5. From the student’s invitation on the outside line, the instructor executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line. In response the instructor seeks to increase degrees of strength in the engagement with a movement of increase and attempts to gain an atajo on their own outside line. The student eludes the movement of increase with a circular cut to the inside cheek with a curved step to the right.

- Movement 1 – Student invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Instructor chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Instructor delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the outside line.

- Movement 3 – Instructor uses a mixed violent and aligning lateral movement in an attempt to execute a movement of increase and place an atajo on his own outside line. In response the student executes an offline movement left to escape the engagement.

- Movement 4 – Student chambers the circular cut with a violent movement.

- Movement 5 – Student delivers the circular cut with a natural movement with a curved step right.

(Movements 3 & 4 may be combined into a mixed movement offline and violent to elude the engagement and chamber the circular cut simultaneously.)

Half Reverse, Circular Cut, & Half Reverse

6. From the instructor’s invitation on the outside line, the student executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right which the instructor intercepts with an atajo on the outside line. In response the student seeks to increase degrees of strength in the engagement with a movement of increase and attempts to gain an atajo on their own outside line. The instructor eludes the movement of increase with a circular cut to the inside cheek and curved step to the right. The student intercepts the circular cut with an atajo on the inside line and executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right.

- Movement 1 – Instructor invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Student chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Student delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right which the instructor intercepts with an atajo on the outside line.

- Movement 3 – Student uses a mixed violent and aligning lateral movement in an attempt to execute a movement of increase and place an atajo on his own outside line. In response the instructor executes an offline movement left to escape the engagement.

- Movement 4 – Instructor chambers the circular cut with a violent movement.

- Movement 5 – Instructor delivers the circular cut with a natural movement and a curved step right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the inside line.

- Movement 6 – Student uses an aligning lateral to deliver a half reverse with a curved step right.

(Movements 3 & 4 may be combined into a mixed movement offline and violent to elude the engagement and chamber the circular cut simultaneously.)

Half Reverse, Circular Cut, & Circular Reverse

7. From the instructor’s invitation on the outside line, the student executes a half reverse to the outside cheek with a curved step to the right which the instructor intercepts with an atajo on the outside line. In response the student seeks to increase degrees of strength in the engagement with a movement of increase and attempts to gain an atajo on their own outside line. The instructor eludes the movement of increase with a circular cut to the inside cheek with a curved step to the right. The student intercepts the circular cut with an atajo on the inside line. The instructor responds with a movement of increase attempting to place an atajo on their own inside line and the student responds with a circular reverse to the outside cheek with a transverse left or a circular step left depending on the distance.

- Movement 1 – Instructor invites with an offline movement left (fingernails up). Student chambers the half reverse with an offline movement left.

- Movement 2 – Student delivers the half reverse with an aligning movement and a curved step right which the instructor intercepts with an atajo on the outside line.

- Movement 3 – Student uses a mixed violent and aligning lateral movement in an attempt to execute a movement of increase and place an atajo on his own outside line. In response the instructor executes an offline movement left to escape the engagement.

- Movement 4 – Instructor chambers the circular cut with a violent movement.

- Movement 5 – Instructor delivers the circular cut with a natural movement and a curved step right which the student intercepts with an atajo on the inside line.

- Movement 6 – Instructor uses a violent and aligning lateral movement in an attempt to execute a movement of increase and place an atajo on his own inside line. In response the student executes an offline movement right to escape the engagement.

- Movement 7 – Student chambers the circular reverse with a violent movement.

- Movement 8 – Student delivers the circular reverse with a natural movement while stepping transverse left or curved left depending on the distance.

(Movements 3 & 4 may be combined into a mixed movement offline and violent to elude the engagement and chamber the circular cut simultaneously.)

(Movements 6 & 7 may be combined into a mixed movement offline and violent to elude the engagement and chamber the circular reverse simultaneously.)