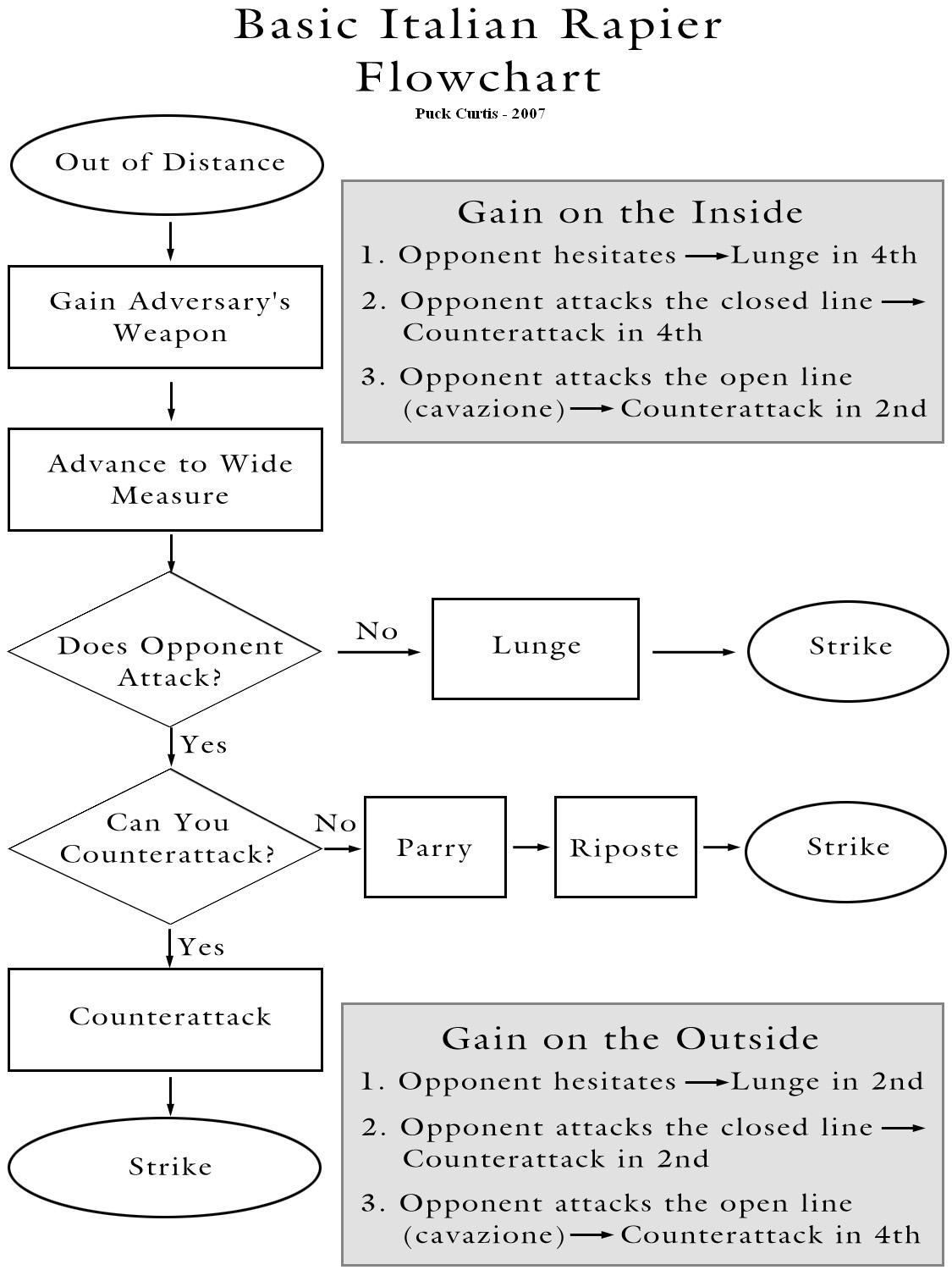

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, Geek Stuff, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier with 7 replies

(11/3/2009)

LINK TO ARTICLE 1

LINK TO ARTICLE 2

LINK TO ARTICLE 3

LINK TO ARTICLE 4

Degrees of Strength in the Weapon

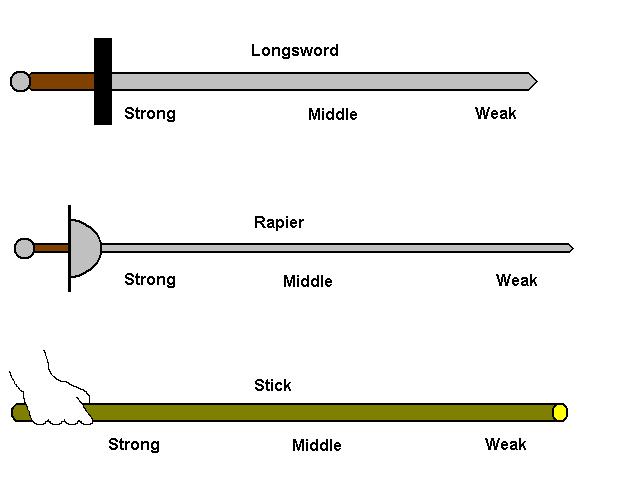

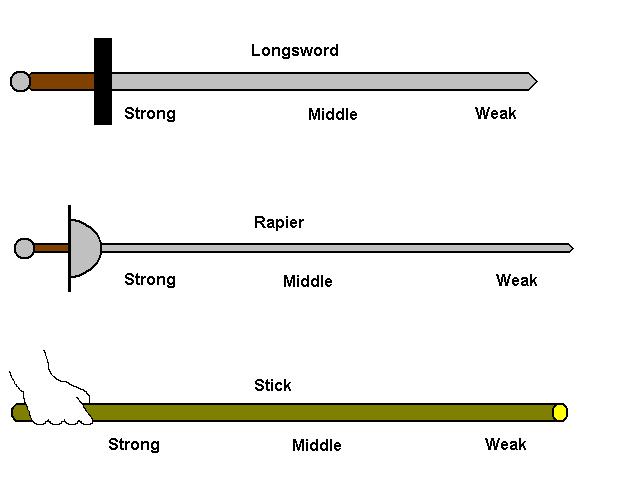

The amount of physical power you can exert with a sword varies along the length of the blade. The part of the blade closest to your sword-hand has the most mechanical advantage and the further you move away from your hand the weaker you become. The Italian system typically breaks the sword down into three parts; Strong, Middle, and Weak. The same will occur for any object held in the hands whether it is a longsword, rapier, or even a stick.

Leverage with Different Objects

While the Spanish understand this and often refer to the Strong and Weak as well, Carranza labels these parts as the Near, the Middle, and the Remote.

Carranza’s Philosophy… f.167 (1569, pub.1582)

| “Know that in the angle of the straight line, the sword has three parts. I mean that its numeration starts from the tip (as we will discuss later), and the strength increases as the numbers are multiplied until stopping in one of the centers. All this graduated quantity is divided in three equal sections with respect to the length, but they are unequal with respect to each one’s quality. You should be aware that the part next to the center’s strength is called near in this Art; the second portion, because it is between the strong and the weak and between the increase and the decrease, is the middle; and the last part is called remote.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

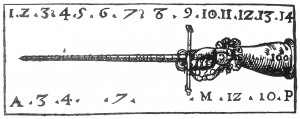

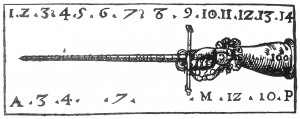

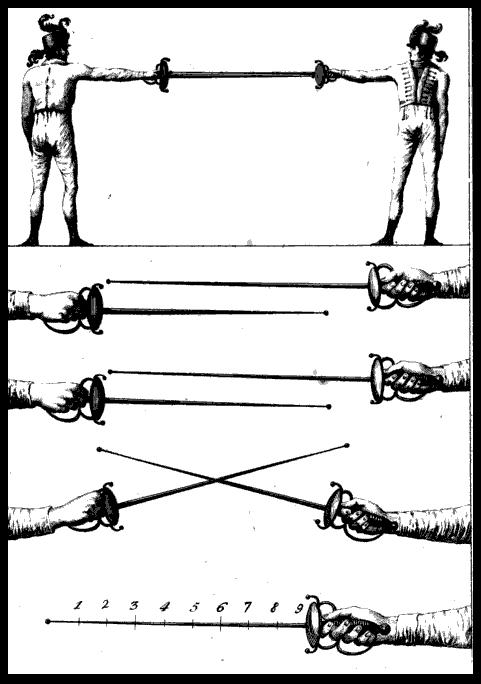

Another method of describing the transition between weaker and stronger leverage is by numbering the sword into degrees of strength. This provides us with more information when describing engagements.

Image from Carranza’s Philosophy… f. 178 (1569, pub. 1582)

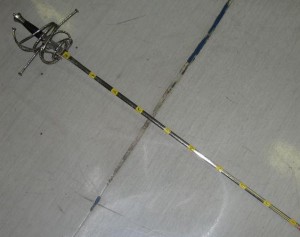

Carranza's Degrees of Strength (Click for High Resolution)

Notice that the blade is numbered from one, the weakest portion, to gradually higher numbers that indicate more strength. The effect of the notation is that higher numbers defeat lower numbers which is intuitive and easy to follow. These graduations of strength in the blade can provide an instructor with a greater degree of specificity when speaking with the student.

“Engage his 4 with your 6.”

“Shift the engagement from your 3 to your 8.”

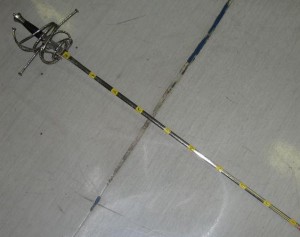

Alonya's sword with the degrees of strength marked in tape for training

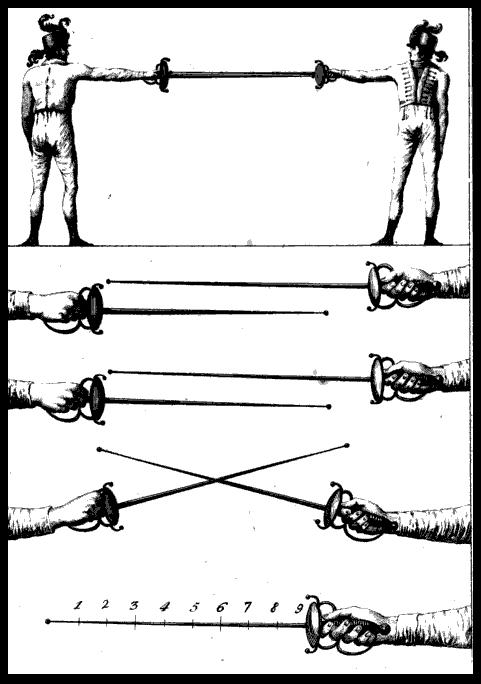

Carranza’s Leverage Demonstration

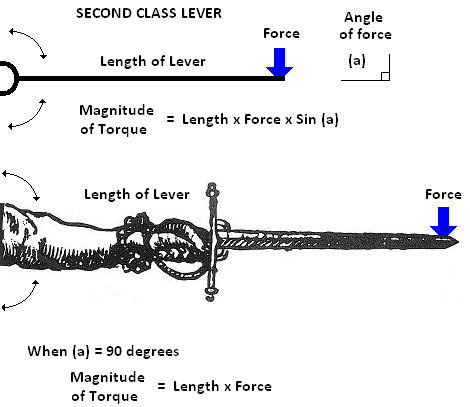

Carranza proves the mechanical advantage by applying a finger to the weakest part of a sword to demonstrate the combined effect of two different types of leverage working simultaneously.

Carranza’s Philosophy… f. 179 (1569, pub. 1582)

| “Then place the first finger of the four (called the index) on the tip of the sword at the beginning of the violent movement, and hold it firm, so that it makes two right angles with the sword. And I tell you all on behalf of the truth that even if many strong arms join together to move it from the place where the finger is, not removing it to the sides nor below, they will not move it. They will not be able to move it upward either nor make a violent movement with it upward in any way, as you all will see in this illustration that serves for the violent and natural movement.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

DANGER: A Bit of Physics…

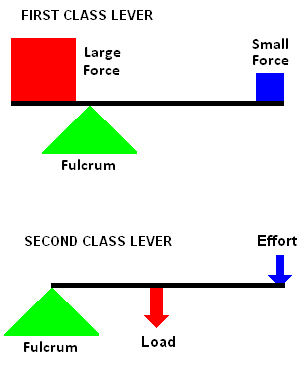

To understand Carranza’s illustration, we must first define torque. When physicists talk about the linear motion of an object, we can talk about forces acting on the object. For example, if I want to move a sword in a line, I can apply a force to the sword for a thrust. These forces might be gravity pulling the object toward the earth, a fencer lifting a weapon from a table, or a lunge pushing the weapon forward.

Just as a linear force moves objects in a line, torque rotates objects around a fixed point. When we wish to rotate an object we apply force to the object to achieve torque. The length of the object (or moment arm) affects how much torque we can achieve with a given force. The further from the point of rotation you can apply your force, the greater the torque applied. Just as you can use a longer wrench to unfasten a sticky lug nut, you can also achieve greater torque by engaging the adversary’s weapon further from the axis of rotation. In plain terms, pressure on the adversary’s weapon in the weak of the blade provides you with much more strength than engagement closer to his hand.

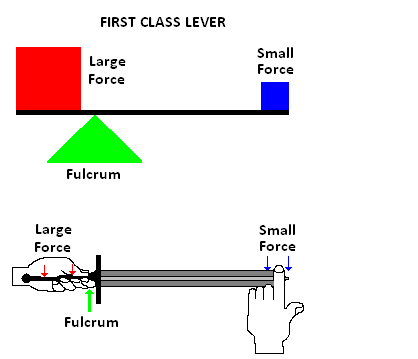

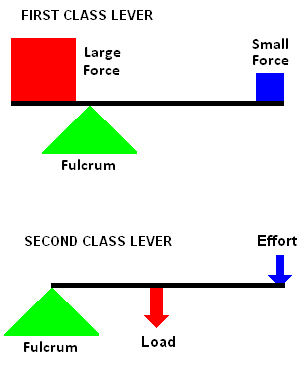

The Most Common Discussed Sword Lever

The weapon will act as a Second Class Lever when the entire arm is considered.

The Sword As a Second Class Lever Hinged at the Shoulder Joint. (The swordarm shown here is a reversed and edited image from Carranza's text.)

The axis of rotation might be the shoulder joint as shown here, or the elbow or wrist instead. Pushing at a 90 degree angle to the sword provides us the greatest amount of torque.

–

Without getting too deeply into mathematics, you can see that when you double the length of the lever, you also double the torque you can achieve with the same force.

- Torque = (1 foot) x (10 pounds) = 10 foot-pounds of torque

- Torque = (2 foot) x (10 pounds) = 20 foot-pounds of torque!!

- (Assuming that both are applied 90 degrees to the moment arm.)

This tells us that if we apply force further away from the shoulder in the weak of the blade we achieve greater torque than the same force applied to the strong.

Example:

You can demonstrate this in your own class by having your largest fencer grip a sword in one hand with an extended arm. Have the smaller fencer apply downward pressure to the tip with a single finger while the stronger one tries to lift the weapon from the shoulder. The large fencer will feel the torque in the shoulder because the entire extended arm and weapon becomes a Second Class Lever. If the large fencer tries to lift from the elbow or wrist, the torque will also be exerted there as well with pressure on every joint resisting the downward motion.

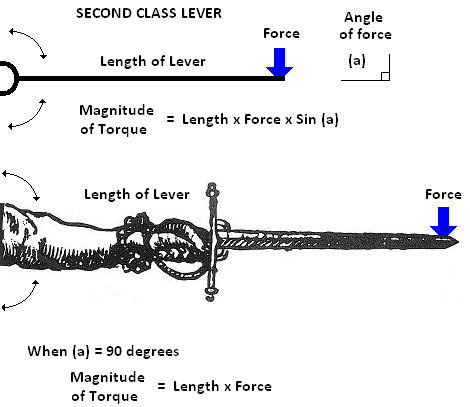

The Hidden Lever

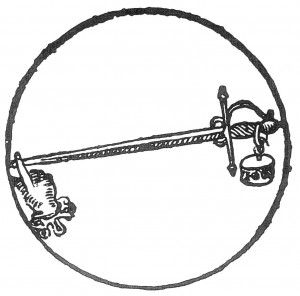

There is another type of lever acting here as well that we can see by looking at Carranza’s image. In this image a heavy weight is suspended from the hilt and with a single finger we can lift it across an invisible fulcrum. What is the missing fulcrum?

Image from Carranza’s Philosophy… f. 179 (1569, pub. 1582)

Carranza's Illustration of Leverage Lifting a Heavy Weight (Click for High Resolution)

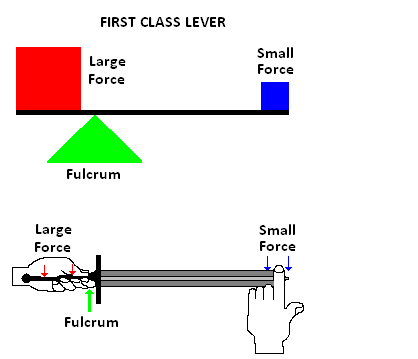

Carranza’s image provides us with an example of the sword as a First Class Lever. The finger on the blade’s weak lifts the heavy weight tied to the pommel with the unseen fulcrum being the hand of the fencer holding the weapon.

The Sword as a First Class Lever held by this left-handed swordsman.

The conflict between the fencer’s gripping force and pressure applied to the weapon is one of the mechanisms you might use to disarm an adversary. For example, in the previous article Carranza indicated that fingernails up is the weakest position of the hand. By applying downward pressure or a strong beat to the adversary’s weapon, you might be able to disarm your opponent. Salvator Fabris shows two possible disarms against an adversary in fourth (fingernails up) in plate 181.

Example:

You can demonstrate this in your own class by having your largest fencer grip a sword in one hand fingernails up. Have the smaller fencer apply downward pressure to the tip with a single finger. The strong fencer will feel an intense amount of pressure at the fulcrum point, and the smaller fencer will probably be able to push the tip downward. If this pressure is applied quickly and with force, it could result in a disarmament.

When Opposition Occurs Natural Defeats Violent

In a natural movement, the blade falls while in a violent movement it rises. According to the Spanish when two blades are in contact with equal degrees of strength, the fencer pushing downwards has the advantage over the fencer attempting to lift his weapon. The fencer pushing downwards can bring the weight of his upper body to bear into the engagement while the fencer resisting from below must rely solely on the muscles in the arm.

Pacheco argues that the Natural movement “…cannot be defeated by another, due to its noble nature,…” and Ettenhard echoes this.

Ettenhard in Compendium of the Foundations… p.89 (1675):

| “…and it is very clearly shown that he [don Luis Pacheco de Narvaez] said it because of the natural movement, since to it alone belongs the subjection, and in conclusion, it alone is superior to all, due to being the noblest, quickest and strongest.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Changing the Relationship of the Opposition

When two blades come into opposition changing the point of contact can increase or decrease your strength in the engagement. Within the Spanish system this would be increasing or decreasing the degree of the sword.

In German longsword the practice of lifting the weapon to change a weak engagement to a stronger one is called ‘Winding’. The Spanish have a similar concept called a Movement of Increase. If both fencers start with equal engagement, Ettenhard tells us that by lifting the weapon and carrying it into the line of offense we can strengthen our engagement.

Ettenhard’s Compendium… p.119 (1675)

| “…the movement of increase, which is made in order to graduate the sword. Since for this reason more strength is acquired and increased, it is appropriately given this name but not because it is of a different type from the ones mentioned in the principles that have been defined, since this action falls (with more certainty than to any other) to the mixed movement aligning lateral and violent.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

In contrast, moving from a strong engagement to a weaker one is called a Movement of Decrease. If both fencers start with equal engagement, then by lowering the weapon and moving away from the line of offense we weaken our engagement.

Ettenhard’s Compendium… p.119 (1675)

| “The movement of decrease is the one that is made in order to reduce the strength, disgraduating the sword, whose action belongs legitimately to the mixed movement of offline lateral and natural…” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

This again reinforces that the high line provides the greatest advantage and that engagement from below is considered weaker by the Spanish tradition.

A Riddle of Inertia, Momentum, and Energy

It might be best to consider a fencer’s riddle and then examine some physics to provide us with an answer.

Riddle: How can you parry a greatsword with a dagger?

DANGER: A Bit More Physics…

Inertia is an object’s resistance to a change in the state of its motion. Any object that is not moving requires force to accelerate it. For example, to swing a cut you will apply a force to the weapon to accelerate it towards the adversary’s head. If we ignore rotational motion in this discussion, the required force is defined as:

Force = (mass of sword) x (acceleration)

In order to decelerate or stop a moving object you have to apply the same type of force.

Momentum is defined as the product of velocity and mass which does not provide us much perspective into its effect in swordplay, but it is useful for determining behavior during collisions because momentum is conserved. That means that a heavy object moving very quickly (like a greatsword) that is forcibly stopped by a smaller one will transfer momentum to the smaller object.

Momentum = (mass of sword) x (sword velocity)

Kinetic Energy tells us how much energy is delivered with an attack. The most important element in delivering a powerful attack is the velocity as shown here:

Kinetic Energy = 1/2 x (mass of sword) x (sword velocity) x (sword velocity)

By plugging in some numbers we can see how this might turn out. First, we can weight the two equally as shown here:

Kinetic Energy = 1/2 x (2) x (2) x (2) = 4

If we double the mass we achieve an increase in energy as shown here:

Kinetic Energy = 1/2 x (4) x (2) x (2) =8

If we instead double the velocity we achieve a much more powerful attack:

Kinetic Energy = 1/2 x (2) x (4) x (4) =16

Carranza Answers the Riddle

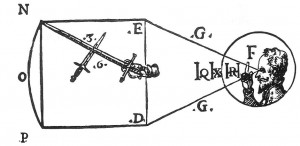

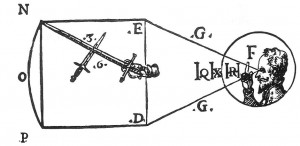

In Carranza’s Philosophy on folio 180 we see an odd figure with a dagger, a sword, a hand, and a head surrounded by geometric figures. (This is one of only six figures in the treatise.)

Carranza's Analogy for Momentum, Inertia, and Energy (Click for High Resolution)

If you close one eye and lift your index finger, holding it away from your face like the man in the image, it obscures only a very tiny portion of your sight. As you bring your finger back towards your eye (the source of your sight) it becomes larger and obscures more. If your finger is close enough to the origin, it can block out your entire view. What this tells us is that even a tiny finger can obscure a large object when it intercepts the vision at the beginning.

Carranza uses this as an analogy to tell us that in the same way, even a dagger can parry a powerful greatsword if it intercepts the cut close to the beginning of the attack. (Looking at the image above you can imagine intercepting the attack where it begins at the point labeled N.) Because the velocity is close to zero it is easy to halt (Inertia), the Momentum is low, and the Kinetic Energy delivered at the beginning of the cut is also very low.

If you intercept the same cut at the point labeled O, the velocity of the attack has increased and your parry can easily fail.

Riddle: How can you parry a greatsword with a dagger?

Carranza’s Philosophy… f.180 (1675)

| “These movements are weak in all their beginnings,… “ |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Answer: Parry the attack when the velocity is zero or very low.

Conclusion

I have used the physics described by Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica to explain some of the different aspects of how a sword functions but this text wasn’t published until 1687. The equation for kinetic energy was not discovered until 1829 by a French mathematician named Gustave Coriolis. Even considering that the fencing masters of Spain used the physics and motion described by classical authors like Aristotle, they knew qualitatively how weapons moved in combat which provides their work with a high level of sophistication.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with 7 replies

(10/1/2009)

LINK TO ARTICLE 1

LINK TO ARTICLE 2

LINK TO ARTICLE 3

Hand Positions

In the Italian tradition the hand positions are notated as first, second, third and fourth. While this is concise, it doesn’t provide any information that guides the student to the correct position without additional explanation. When grasping a sword, we can discuss the same hand positions by the orientation of the fingernails. By using the fingernails as a reference, the Spanish system achieves a very simple notation for the position of the hand in plain language.

Fingernails Down (uñas abajo) – The edges are in the horizontal plane with the true edge on the outside line and the fingernails facing downward. This is the same as Italian Second. Carranza considers this position one of the two possible extremes that will be weaker than the moderate halfway point between this position and fingernails up.

Monica's hand is fingernails down.

——————————

Fingernails Inside or On Edge (uñas adentro or de filo) – The edges are in the vertical plane with the true edge low and the fingernails facing toward the inside line. This is the same as Italian Third. Carranza considers this the best position and it is halfway between the two extremes of fingernails up and fingernails down.

Monica's hand is fingernails inside.

——————————

Fingernails Up (uñas arriba) – The edges are in the horizontal plane with the true edge on the inside line and the fingernails facing upward. This is the same as Italian Fourth. Carranza considers this position one of the two possible extremes that will be weaker than the moderate halfway point between this position and fingernails down.

Monica's hand is fingernails up.

—————————–

Fingernails Outside (uñas afuera) – The edges are in the vertical plane with the true edge high and the fingernails facing toward the outside line. This is the same as Italian First and while it is mentioned, using this hand position is so unusual that Pacheco and Carranza typically speak only of the other three.

Monica's hand is fingernails out.

Hand Position in the Spanish Stance

The primary sources indicate fingernails inside or sword on edge is the hand position used when assuming the stance.

Carranza’s Description of the Position of the Sword Arm from The Philosophy of Arms… p. 155-156 (1569, pub. 1582):

| “And the best of all these positions is as the arm originates because in it the nerves are more relaxed and the action of the Muscles—which are (as it is said) the instruments of the voluntary movement—quicker. In this position the strength endures longer, and since it is the middle (according to necessity) one passes easily to the extremes. For these reasons and others that come from these, the position on Edge is stronger and better than the one with fingernails down or up. Between the extremes there is advantage, like in those extremes that the virtues have (as we will mention in its place), because the extreme that the Fingernails Up arm makes is not as strong as the position of Fingernails Down. Thus, of the two, Fingernails Down is the most noble because it strains the Nerves less to maintain the strength, because even though the arm does not move (seemingly) the Muscles are working inside that maintain it in that position….” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

To explain this passage, hang your swordarm normally at your side and then reach forward as if shaking hands. A natural extension places the weapon arm as it “originates” with the fingernails facing the inside. If you extend your arm with the fingernails in you are halfway between the extremes of fingernails down and fingernails up which allows you to engage with your true edge quickly as needed.

You should also note that the text explicitly indicates fingernails inside is stronger than fingernails up and fingernails down. Coming into guard fingernails up or fingernails down contradicts the author which is our primary source. Carranza provides us with a ranking of the hand positions with fingernails in as the best and fingernails up as the least strong or worst of the three.

- Fingernails in or sword on edge (Best)

- Fingernails down (better than fingernails up)

- Fingernails up (worst and least strong)

(Carranza does not discuss fingernails outside in this passage and by its omission we might assume it would qualify as the least useful position.)

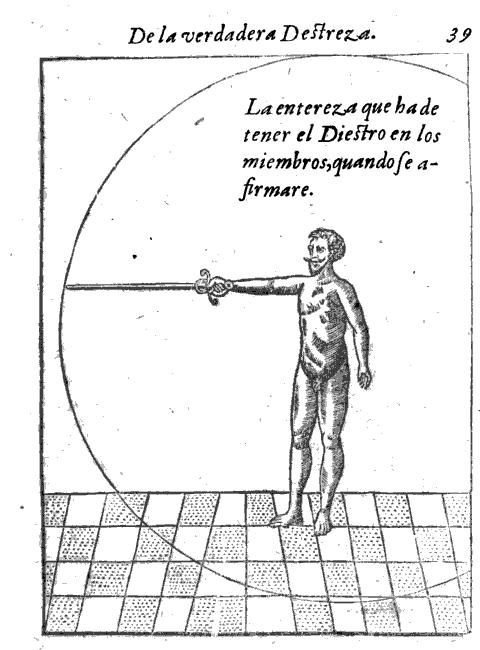

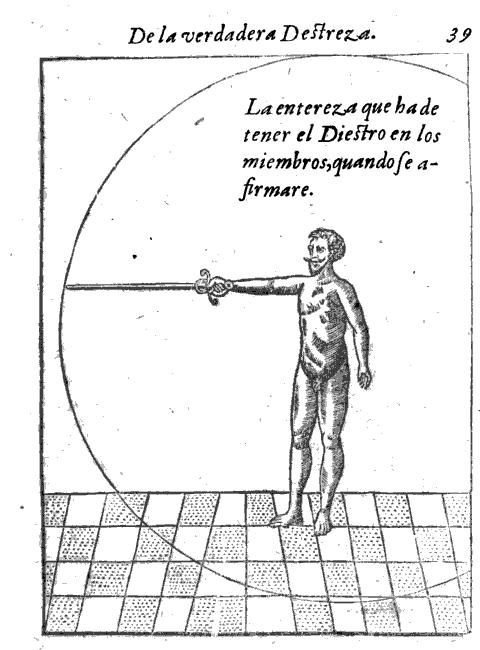

Pacheco’s Image of the Stance from The Book of the Greatness of the Sword p.39 (1600)

Pacheco's Stance showing the hand with the fingernails inside.

Pacheco again in New Science p.30 (1632)

| “The right angle is seen with the body being straight, and over the right angle or over the parallel lines, and he extends the arm straight as it originates from the body, without lowering it nor raising it.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Ettenhard’s Description of the Position of the Sword Arm from Compendium of the Foundations… p.13 (1675)

| The first thing that one should deal with is the way to form the Angles, with the application of the Geometric measurements; and beginning with this, I say: That the Swordsman forms the Right Angle when he stands with the body straight and perpendicular; as he naturally falls over both feet, leaving a half foot distance between one heel and the other; and then holding out the arm and Sword straightly, like it originates from the body,… |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Over 100 years later, we see that Ettenhard comes very close to quoting Carranza in his description of how to assume the stance with the arm extended “like it originates from the body“. When comparing the text to the relevant image in Treatise 2, Chapter 1, we see Ettenhard’s fencer with the hand fingernails inside which further confirms the interpretation.

Brea’s Images in Universal Principles… Ch12.L7 (1805)

In 1805, Manuel Antonio de Brea shows the stance in his book again with the hand fingernails to the inside.

Brea shows the hand position in the stance with the fingernails facing inward for this demonstration of the Measure of Proportion and the Degrees of Strength in the weapon.

You can view Brea’s Universal Principles and General Rules… online with Google Books here:

Thibault’s Academy of the Sword Ch43 – Plate 12 (1630)

Even Girard Thibault, who is arguably outside the mainstream Spanish canon, demonstrates his stance with the hand fingernails in. Because of the peculiarity of his grip, Thibault’s cross is aligned in the horizontal plane, but the hand again follows Carranza’s advice extending as the arm originates with the fingernails facing the inside line.

Thibault's stance with the hand fingernails in and the cross in the horizontal plane

Wikipedia Article with two images of Thibault’s intricate plates

Conclusion

The repeated examples in both the texts and original images provides compelling evidence that assuming the stance with the weapon hand in a position other than fingernails inside would be a significant deviation from the tradition. While the hand position may naturally change in the course of an encounter by starting between the two extremes of fingernails up and fingernails down, the Spanish fencer is able to quickly change the position of the hand to align the true edge as needed while fencing.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, Geek Stuff, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier, Opinion with 11 replies

(9/28/2009)

Image from Swetnam

“…yet regard chiefly the words rather than the Picture.” ~ Joseph Swetnam

First, a postulate is to maintain or assert that something is self-evident. It is part of the fundamental element or basic principle of a logical argument.

Second, a primary source is an original text (like a fencing manual) or an object (like a sword). We will use a primary source to draw conclusions about a topic. A fencer might study the book of Salvator Fabris to understand Italian rapier. Darkwood Armory might study a rapier from the original time period to understand how to create a training weapon for fencers today.

In our case, a primary source is important in identifying the origin of the information we want to interpret. Primary sources are given greater value than secondary sources. A secondary source is information or discussion of the primary source that is not originated from the primary source. For example, you could argue that our recreation of Destreza based on an English translation is a tertiary source because it is based on a secondary source (the English translation).

This becomes tricky in a fencing manual when we consider the images. For example, Ridolfo Capoferro’s work has been subjected to some intense scrutiny in this regard and I have been involved in some heated discussions about the position of the feet, the nature of offline steps, and the gaining of the weapon. While the plates in the text are very important we need to remember Joseph Swetnam’s advice.

“…yet regard chiefly the words rather than the Picture.”

I call this Swetnam’s Postulate. Unless the fencing master himself is listed as the artist, the images are not a primary source of information but rather a secondary source.

Interpreting a Text

When interpreting a fencing text, I use a hierarchy of sources in which item 1 is given the highest priority and item 7 the lowest.

- The text in the original language is a primary source.

- Swetnam’s Postulate – Unless we can prove the master created the images, the artwork is a secondary source.

- The translated text is a secondary source.

- Masters in the same tradition, weapon, and time period can provide insight to technique.

- Masters in the same tradition, weapon, and a different time period, can also provide insight.

- Masters in the same tradition with similar weapons (for example classical Italian fencing) can provide insight.

- My own experience or experimentation.

For example… If Capoferro indicates that I should travel directly forward on the line of direction, I should obey the text even when it contradicts (or seems to contradict) the images rather than reinterpret the author’s instructions based on my understanding of pictures created by an artist. If other sources within the tradition also seem to confirm Capoferro’s text, rather than a picture that could arguably be on the line or off it, this provides us additional incentive to trust the author’s voice.

Likewise, as an interpreter, I need to be aware of my fencing biases and try to avoid item 7 as much as possible. When I change ‘canonical‘ technique or add technique of my own this needs to be clearly stated in my interpretation. (In this sense, I use the term ‘canonical‘ to indicate a deviation from the original text or texts.)

For example, at WMAW 2009 I applied principles from Ettenhard’s book in order to create new techniques appropriate for left-handed fencers. When I demonstrated these variations to the class, I made certain to explain that these were my variations and not Ettenhard’s original work.

By expressing some dissatisfaction with the images in his book and asking the reader to give his words precedence over the plates, Swetnam reminds us that the author’s voice is the first and primary source of information an interpreter should consider.