You are reading the archive for the category: Destreza (Spanish swordplay)

Filed as Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with no replies

The General Tretas

The General Techniques (or Tretas) carry or capture the opposing weapon by creating a spiral with your own weapon.

|

|

Inside Line

(Spiral Counterclockwise)

|

Outside Line

(Spiral Clockwise)

|

|

Half Circle Spiral

|

General Technique of Narrowing

(Thrust by Glide)

|

General Technique of Weak Under

Strong

(Thrust by Detachment) |

|

Full Circle Spiral

|

General Technique of Weak Over

Strong

(Thrust by Detachment) |

General Technique of Line in Cross

(Thrust by Glide)

|

NOTE: All the descriptions below assume the opposing weapon is carried by the spiral instead of captured.

General Technique of Narrowing:

From an atajo on the inside line at MdP*, carry the opposing steel in a half

circle counterclockwise to the outside low line and terminate by stepping to

the right to deliver a gliding thrust to the chest.

General Technique of Weak under Strong:

From an atajo on the outside line at MdP*, carry the opposing steel in a half

circle clockwise to the inside low line and terminate by stepping to the right to

deliver a thrust by detachment to the chest.

General Technique of Weak over Strong:

From an atajo on the inside line at MdP*, carry the opposing steel in a complete

circle counterclockwise to the inside high line and terminate by stepping to

the right to deliver a thrust by detachment to the chest.

General Technique of Line in Cross:

From an atajo on the outside line at MdP*, carry the opposing steel in a

complete circle clockwise to the outside high line and terminate by stepping to

the right to deliver a gliding thrust to the chest.

Addition: The Generals can be combined together in such a way that the end of one may form the beginning of another without breaking the spiraling motion.

*MdP = Medio de Proporción or the Defensive Medio\Place.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with no replies

Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez

He is acerbic, often dogmatic, and difficult to like. Pacheco’s work at first glance would not seem to be an ideal metric by which to unify a tradition. Many people reading Pacheco for the first time have a strong negative reaction to the trollish way he jibes at the works of others. He does not resist the urge to throw punches in his prose and perhaps it makes him an early species of today’s internet troll who pokes and annoys others for his own amusement. Reacting to his tone, we might quickly dismiss him but the problem is that Pacheco is also an incredibly gifted technical writer and theoretician who is perhaps the most prolific fencing author in history. Most of the technical information we currently have about La Verdadera Destreza is a direct or indirect result of Pacheco’s work.

Carranza’s work does not contain enough technical material to describe a complete system. Thibault’s work is both extensive and technical but appears to be out of sync with the other authors. Most of the other La Verdadera Destreza authors available are derivative of Pacheco’s core system which means they are in some sense accountable to his examination standards. For this reason I often find myself presenting or defending Pacheco’s position as a common point of verifiable evidence even while I acknowledge that the tradition is broader than a single author.

The classical tradition that trained me enforces a core standard of practice with meticulous care. As an example, the hand in the invitation of second shall be held at a certain height and angle; to do otherwise is incorrect. However, if we examine the historical record, we see a multitude of different examples of the invitation in second and it might seem that this insistence on uniformity would be a compulsion which also borders on trollish antagonism towards the students. Why? What purpose does it serve?

By reducing scope in the school and during the examinations it creates right and wrong answers. That brief state of artificial purity allows students to develop their core skills and to carefully climb within a demanding system from ignorance into technical competence. As the students develop understanding and ability their own questions naturally arise which challenge the purity of the right and wrong answers.

An Instructor candidate should be able to recite the answers in the textbook and teach most of the actions described. The Provost candidates teach at a higher level and might qualify their answers, delve into difficult and broader theory, and occasionally explore concepts outside the textbook. The Master candidate is expected to not only be able to teach the textbook in its entirety but to also know when to leave it aside and justify the reasoning. The mastery of the lesson and execution becomes a personal expression which realizes the tradition as an act of creative art. An answer outside the scope of the book can become correct when good reason and judgment are applied.

William Gaugler’s fencing master’s program was not cloning human versions of his textbook but rather creating a common language and understanding by which a community could work outward to achieve nuanced understanding which could be both broad and deep. This might best describe the position from which Figueiredo wrote his Oplosophia; he has enough knowledge and expertise to master a tradition and yet uses his ability to provide critical expertise on the elements involved which challenges the canon of the tradition itself.

It is within this textbook form that Pacheco’s work shines. We have his proposed testing criteria and a large body of work which we can use to create a uniform standard for examination. A student citing Pacheco in his examination works from a defensible place of canonicity which provides a textbook of right and wrong answers. It forms a common core of theory and practice from which the students may safely learn in an elegant simplicity and ultimately transcend into multi-hued complexity.

Pacheco is not the only voice in our tradition but he is one of the great LVD authors and just as the textbooks in the classical program provide a beginning, mastery involves internalizing the work and seeing beyond the rules into the deeper and changing causes from which they are derived. Studying Pacheco diligently can become a Carrancine exercise in the search for verifiable science which can be taught and demonstrated.

For a Carrancine teacher Pacheco serves as a brilliant starting point, as a tool for teaching and examination, as an exercise in application, and as a historically uniform standard for evaluating knowledge and practice. Pacheco is a ready-made roadway from ignorance, through competence, into mastery. When that path is paired with Carranza’s instructions about teaching, science, art, and ethics we move from creating builders into creating architects.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier, Opinion with no replies

There is no point in dreams if they lack some measure of audacity.

It was January of 2000 and the world had survived the millennium bug. The place was Breckenridge, Colorado and a member of my wife’s family had a cabin near the ski resorts. There at the top of the mountain I got my first bit of instruction in the ancient art of skiing.

The first and last thing I heard was, “Lean forward,” and so I did. I began to slide down the mountain gaining speed. I had no way to steer and no idea what I should be doing. I found myself completely out of control and was headed towards the trees at increasing velocity. Before I painfully crashed I orchestrated a controlled wipe-out into the snow with poles, skis, and limbs all flying in different directions. The remainder of the day was a repeat of the same series of leanings forward with various wipe-outs. I got better instruction and learned how to stop by “snow-plowing”. By the end of the day I had learned how to turn and stop with the skis parallel.

Sometime ago I became interested in the study of incompetence and how incompetent people generally behave. Specifically I was interested in the meta-cognition of incompetence as studied by Justin Kruger and David Dunning who found that incompetent people were unable effectively to evaluate their own competence. This lack of ability to understand personal competence has been called the Dunning–Kruger effect and restated basically it means that incompetent people tend to overestimate their own level of skill.

Link to the study:

https://www.math.ucdavis.edu/~suh/metacognition.pdf

(For an academic study, this is riveting material to read especially as a researcher, teacher, or student of martial arts.)

Compare that to Carranza’s statement, “He who knows most doubts most.” Carranza adds the perfect corollary to the DK effect and uniting the two ideas has given me a basis for moving forward during difficult tasks. (As an example, when a prairie-born Okie is rolling down a mountain with skis tied to his feet.)

The point isn’t to belittle or slander incompetence; we’re all incompetent in some subjects. Instead, my goal was to develop strategies to understand and mitigate my own incompetence by reserving a healthy dose of doubt about my own ability and creating a series of tests to validate my own performance.

I am going to add my own rule which I learned in Breckenridge, “Lean forward.” We can paraphrase Voltaire to arrive at a similar statement, “Never let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” If I had become paralyzed with the fear of the many stumbles, spectacular wipe-outs, and public laughter at my misbegotten antics I might never have learned to ski that day.

We might best understand this as a Medio (or a virtuous mean or balance point as Aristotle and the Destreza authors might describe it). There is absolute perfection at one extreme. At the other extreme is complete incompetence. Between the two extremes is the good work we might do if we just lean forward and accept our imperfection.

We need to teach and practice La Verdadera Destreza to build our skill and to foster a community. But, we also know not all the work has been translated which should be a warning to us to preserve our doubts. Previous attempts have stumbled and fallen quite publicly. Worse, our mistakes may be mocked and picked apart and ridiculed by our peers.

1. Know that your ability to self-evaluate is shaky while you are learning.

2. Preserve a healthy doubt and create meaningful checks to ensure your work is good.

3. Lean forward and be ambitious unto audacity. Don’t let the fear of failure prevent you from producing work.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier with no replies

Like many of the stories of my life, this one should start with me being a fool. It was WMAW and assembled there were a collection of instructors trained through Maestro William Gaugler’s fencing program. The Chicago Swordplay Guild wished us to deliver to Maestro Gaugler a gift. Resting inside a carved box was a wooden gladius, a Rudis, of the kind which was traditionally presented to a gladiator who had earned his freedom to become a Rudiarius. Engraved were words expressing their desire that this tradition should persist forever.

Maestro Gaugler

At the time I thought it was merely a lovely gesture for his years of hard work but this was a young man’s thinking… it was a fool who could not see the message contained therein which we must all face as fencers, teachers, and members of a martial tradition. What I did not know was that Maestro Gaugler was dying and that his days of servitude to the tradition were ending.

In 1979 Gaugler started the San Jose Fencing Master’s Program which harkened back to an older expression of the tradition in which the inquartata and the passata sotto were still taught. It was taught as if the weapons had greater mass than the trainers themselves actually possessed. The parries emphasized defensive power over the quick ripostes favored in sporting competition. It was a school in which we were required to both percussively strike and then slice in our sabre cuts in order to lay open wounds we would never see. The sabre cuts circled from the elbow to generate enough force to deliver powerful cuts while withdrawing our forearms from the threatened space created when the weapon left the line of offense. It was heavily based on Parise’s work which was itself an attempt to protect the Italian tradition. In order to certify the Fencing Master’s program Gaugler brought masters from Italy to witness the exams and they did so expressing their admiration that he had created so authentically an Italian expression of the art.

Gaugler had created a time capsule waiting for the right moment to be opened. Outside of Gaugler’s Italian time capsule competitive fencing had moved in a different direction but a new movement lay on the horizon and the historical fencing community arrived at the end of the millennium. I had been working on historical traditions for over 10 years before I began studying under the masters that Gaugler had trained. The fencing master’s program was based on a martial system which was well-documented but even more compelling for me was a tradition of teaching which was largely unknown outside the school itself. As I began to train, my own understanding of the historical texts and my ability to transmit the material to students began to accelerate. Not only was my own practice getting better but my ability to train an effective historical Italian fencer had begun to blossom.

The Spanish Destreza author Carranza describes the early rudiments of knowledge as trying to write a letter while knowing only ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’. Having found the Gaugler-trained masters I was awash in a rich language which I had never seen before and I was beginning to write fresh prose as I received the hundreds upon hundreds of touches from my students. Every lesson I gave changed the world in some small way and I was creating fencers who were both powerful fencers but also mastering a systematic way of approaching their martial tradition.

Gaugler’s insistence that lesson be the mirror of combat, that our classwork artificially preserve the mass of actual weapons, had created a clean bridge from the classical tradition into the earlier rapier work and the results were impressive. In my younger days I was a competitor in my fencing. I fought for the love I had of friendly play and the joy of the art itself. Fencing is so often an art form that lasts but for a brief shining moment which transcends all our human imperfections to create an instant of perfect time. What a joy it is to be there and to see the light it brings to the world.

Today I more often work on helping others to kindle their own spark. The day will come when I am held to task for what I did to preserve the traditions in my care. Did I create new and useful work? Did I train new fencers and teachers? Have I done everything in my power to ensure the tradition will persist forever?

I am a thing so well out of his place stumbling and making errors in my work as I strive to rebuild the Iberian traditions and protect the Italian ones. In that sense, being a fool is one of my strengths for I persist in striving regardless of my mistakes in the hope that I can do better. Being publicly wrong and taking the bruises required to correct my fumbling is a cost I will pay if it means the traditions endure. I am a fleeting, temporary thing but I am mindfully working to create a new generation of fencers and teachers who will carry the torch forward. The measure of my worth is not the adversaries I have defeated with my tradition but rather the students and teachers I have given to my tradition.

On December 10, 2011 William Gaugler died. Before the doors were closed on his program it had created 18 masters, 31 provosts, and 47 instructors. His gifted Rudis was a message from a grateful community to the Maestro; it contained a release but also a promise that we would carry his burden going forward so that the art would persist. Your work is done Rudiarius; rest easy.

Books by M. Gaugler

Filed as Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with no replies

What is an Atajo? To understand the Atajo it is useful to understand the primary causes that make it work.

I’m intentionally going to present this from the perspective of a Pachequista (a follower of don Luis Pacheco). Pacheco literally defined the fencing master’s examination in Spain so in this regard his work is “canonical”.

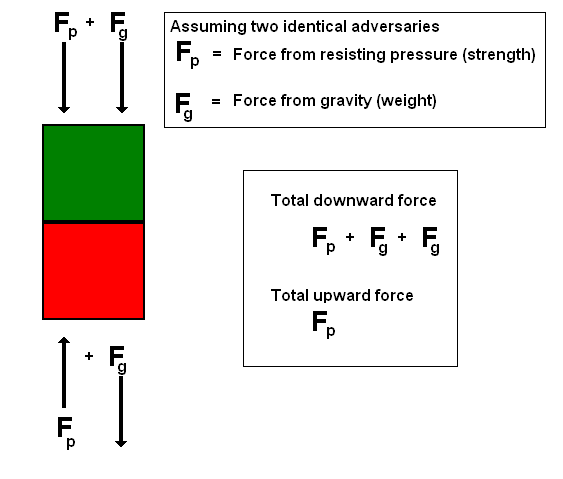

The Advantage of Downward Pressure

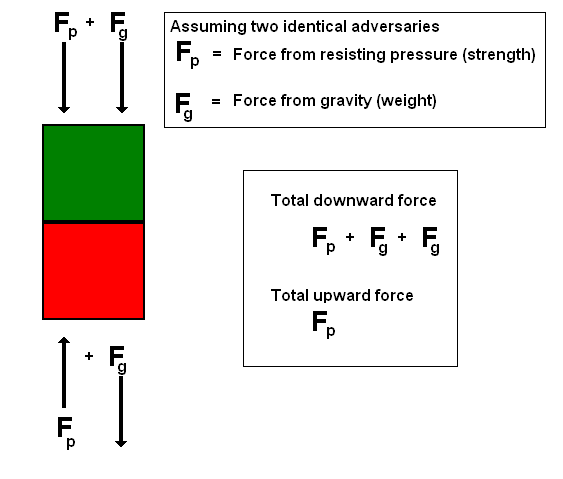

If I extend my arm out toward you with the palm up and you press down while I resist you will probably be able to lower my arm. The Spanish call this the superior nature of the natural movement (descending) versus the violent movement (rising). Your own body also provides an advantage when you use your shoulder and body to assist in the motion to increase the downward force.

Principle: If all other factors are equal a downward force will defeat an upwards resistance.

When two equal adversaries resist each other, gravity lends a hand.

The Advantage of Degrees of Strength

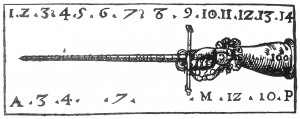

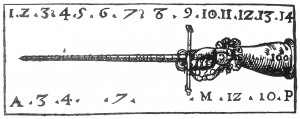

I have already written an article about blade mechanics, but every swordsman worth his or her salt should already know that in contact between two weapons, the swordsman with superior degrees of strength in the engagement has an advantage of power both offensively and defensively.

Principle: When two swords oppose each other in an engagement, the weapon with greater degrees of strength is stronger and has an advantage.

Carranza's degrees of strength showing higher values as stronger.

For more on strength in engagements consider this article:

Spanish Fencing Notation 5 – Strength of the Weapon

The Advantage of Time

When two adversaries act against each other the swordsman who can finish execution sooner has an advantage in time. The Spanish use Movements as a tool for understanding time. When the adversary’s attack requires three movements, he can be defeated by a defense or counteroffense which uses a single movement. In addition an engagement that completely closes a line can limit the adversary’s offensive options to ensure that the time advantage is maintained.

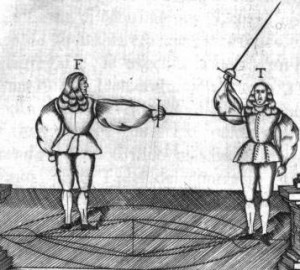

Principle: A defensive action that requires a single movement can defeat an offensive action with more movements.

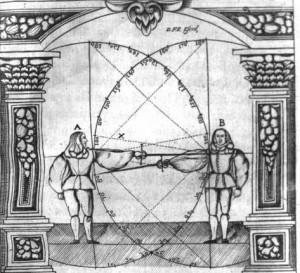

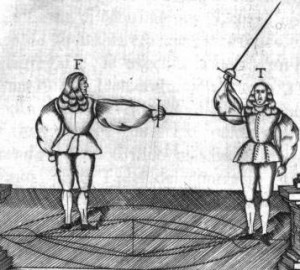

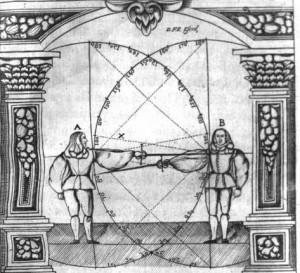

When the adversary attempts to strike with a circular reverse (3 movements) the defender answers with a thrust (1 movement). (Ettenhard Plate 11)

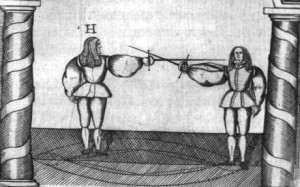

Principle: An engagement which prevents the adversary from attacking in a single motion provides a defensive advantage.

By closing the line, he forces the adversary into a time disadvantage. (Ettenhard Plate 15)

For more on Spanish Movements consider this article:

Spanish Fencing Notation 1 – Vector Notation

Advantage by Domination of the Shortest Path

The Spanish fencer starts with the arm extended and the weapon pointed at the adversary along the most direct path to the target. Knowing that it is easier to push downward then to resist upward, I can use this principle to deny my adversary the shortest path to my body by pushing his blade down. Not only do I increase the distance he must travel to strike my body, I also ensure that my offensive path is shorter and closer to the target.

Principle: By starting with the arm extended along the shortest path to the adversary and then deviating the adversary’s weapon downward you ensure your own path to the target is shorter.

Note: Deviating the opposing steel laterally would be called a desvio or a deflection.

The advantage of the shorter path (Ettenhard Plate 9)

Atajo Defined

The Spanish Atajo unites all of these ideas into a single defensive action which can protect the swordsman while simultaneously providing opportunities and the place from which to strike with safety. Offensively, the atajo can be used to prepare a safe attack that controls the adversary’s weapon. (We would call this preparatory action “dispositive” and the attack “executive“.)

Pacheco in New Science p.365 (1632)

| “Atajo, according to our definition, is when one of the weapons is placed over the other (not in any of its extremes nor with any of its extremes) and with equal or some degree more of strength subjects it and makes it so that the technique that can be formed must be done with more movements and the participation of more angles than those that its simple nature requires.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Pacheco in New Science p.368 (1632)

| “Arriving, then, to the perfect formation of the atajo, it should necessarily consist of three movements: violent, offline lateral and natural. With the first the sword that should subject is placed on a superior plane to the other, with the second it is placed transversal over it, and with the last it subjects it:” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Ettenhard in his Compendium and Foundations… p.154-155 (1675)

| “I am very safely confident that one will have recognized with enough satisfaction that the Atajo causes its effects by means of a superior graduation and of the superior power of the Natural Movement and also that one will concede to me that if it were possible to beat and destroy these two causes, we would see dispelled the end of such superior effects…” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

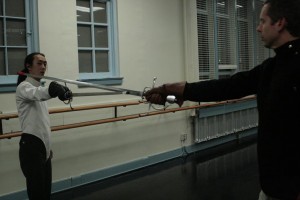

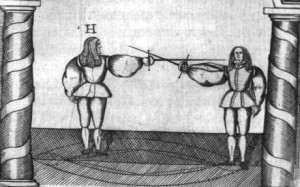

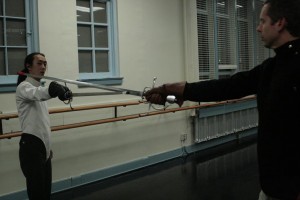

Eric places an Atajo over Kevin's sword. (Click for larger image)

The Defining Elements of Atajo

Between Pacheco and Ettenhard we find these three items essential in placing Atajo:

- Subjection with equal or greater degrees of strength.

- The subjection is placed from above.

- The subjected line is closed so that an adversary cannot strike with a single movement.

When Lorenz de Rada writes later, he adapts the atajo so that you initially seek the subjection from above and if you don’t find it or feel that the adversary is weak in the engagement you immediately spiral towards the opposing steel and closing the opposite line from below. Compare this to the classical transports of 3rd and 4th from high to low or the corresponding half-circular parries from high to low.

Conclusion

This information tells us that Pacheco’s Atajo should start by seeking the superior line with greater degrees of strength in the weapon. The defensive action subjects downward to lengthen the adversary’s path to the target while ensuring your own path is shorter. It might be tempting to equate Atajo with classical engagements but this violates the primary causes of Atajo. Likewise, by definition two swordsmen cannot both have an Atajo simultaneously.