Skill Progression in Fencing

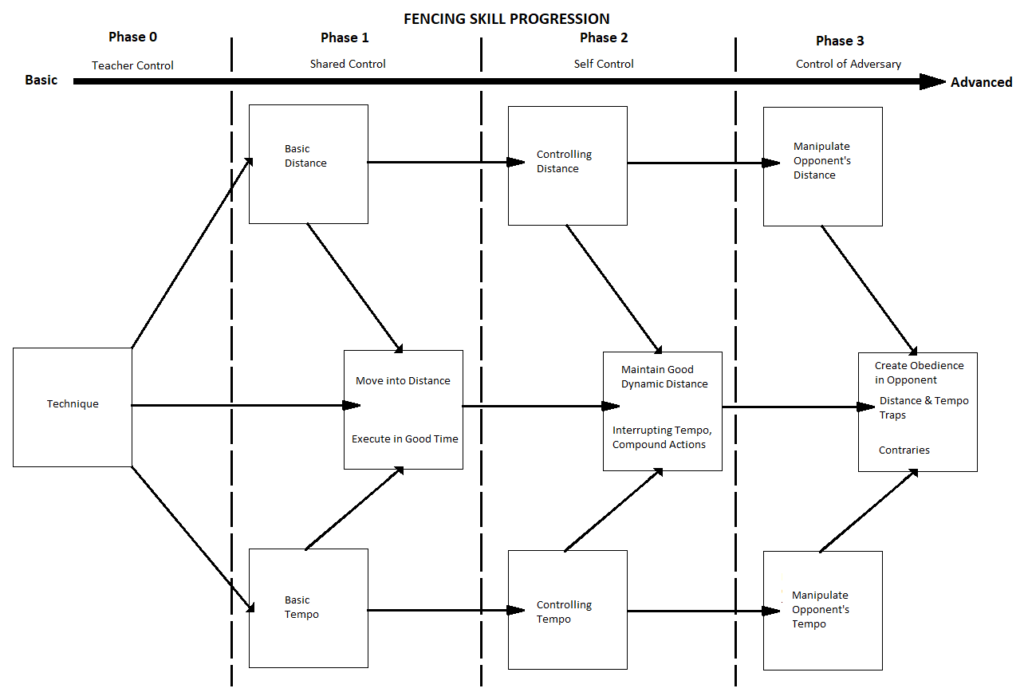

Reading the Skill Progression Chart

This chart depicts the student’s expectations and provides one rubric for evaluation and guiding the progress of a fencing student. (This is not intended to be the single unifying truth of fencing but may provide a useful model for teaching students and evaluating their ability.)

When a student begins with a new skill, they typically lack the ability to correctly use time, distance, and technique to execute an action.

- Top Row – Distance

- Middle Row – Technique

- Bottom Row – Tempo

When working with a beginning student, the instructor can set considerations of tempo aside, manage the distance themselves, and concentrate on fundamental execution of technique. However, to progress to higher levels execution of technique there are gateway skills in the Distance and Tempo lanes which are required to execute fencing actions.

An advanced fencer working with a teacher may begin with a new skill in Phase 0 but their ability to progress is aided by their previous experience. Specifically, when introducing new technique, it is perfectly acceptable (and even recommended) that the instructor set the distance and set aside tempo considerations until the mechanical aspects of the actions are correctly executed. As the student demonstrates technical proficiency they move to higher phases in which distance and tempo are used to execute at a higher level.

“Why doesn’t this work when I am fencing?”

In addition, if your student is having trouble moving from training to effective fencing this progression may provide some insight into the key skills that allow the student to execute actions that are effective.

Phase 0 – New Skill and Building Fundamentals

Distance: The instructor sets and manages the distance.

Tempo: Fighting tempo is secondary to technical execution of the fencing action being learned. Actions are often broken into multiple tempi to facilitate learning key skills at a mechanical level.

Technique:

Offense: The instructor may ask for extension of the arm, then firing of the legs for the lunge. Is the arm first? Is it fully extended? Is the touch being delivered with the correct pressure, hand position, line closure, bend in the weapon?

Defense: The instructor may ask for a pause between the parry and the riposte. Are the parry’s blade and hand position correct? Did the student sink during the parry? In the riposte is the student extending the arm or trying to post over the front leg by lifting the rear heel? Are they creating effective ripostes by glide? Is the closure of line correct?

Phase 1 – Developing Skill

Distance: The student may be asked to use an advance to reach correct distance. The instructor and student will work together to find correct distance for each action, the student’s effective range for attacks, and learning the range of the adversary.

Tempo: When technical execution is correct, the pair moves into training martial tempo. Actions which were broken into pieces for technical training are blended into faster and more martially correct tempi. Attacks must be delivered quickly such that there is a noticeable impact and parries must be able to defeat attacks at speed.

Technique:

Offense: The lunge will be delivered on a single command with the arm extending first every time. The instructor and student together will develop speed, violence, balance, length, and coordination of the attack. The advance lunge will be used to develop the student’s sense of distance.

Defense: Parries must wait until the last possible moment. Ripostes must immediately follow the parry like lightning. The student is expected to elude the instructor’s parries with attacks by disengagement executed in the tempo of the instructor’s attempt to parry or seize the blade.

Phase 2 – Applying Skills to Fighting

By using probing actions, the student draws information from the adversary to determine their preferred attacks, parries, and likelihood to counterattack. The student uses actions of concealment to hide this information from their opponent. Before fencing the student evaluates the opponent based on their knowledge of the adversary to develop a bout strategy and within the bout adapts to the situation using tactics informed by the strategy and the information gathered from probing actions.

Distance: The student learns to train with mobility and is responsible for finding and preserving their distance. (The instructor asks the student to maintain distance as they perform unrehearsed footwork and then cues the student’s action.) The advance lunge is tied to compound fencing actions (feints, actions on the blade, renewed attacks), and the coordinated step is introduced.

Tempo: When martial tempo is achieved this skill is leveraged to develop feints, interruptions, and reversals of the opponent’s fencing actions. Examples might include attacks into preparation and counterattacks. The student is expected to develop control of not just their own tempo but the ability to read, respond to, and interrupt their adversary’s tempo.

Technique:

Offense: The control of tempo and distance means that the student begins to execute effective feints, and compound feints which cause the adversary’s defense to collapse, actions on the blade which dominate or deviate the weapon, and renewed attacks which take advantage of hesitation in the adversary. The student begins to mix and match all of these while developing the ability to press forward and apply pressure to the opponent. The student and instructor developing deeper fencing phrases consisting of multiple actions chained together and tactical exercises in which actions must be chosen in the moment.

Defense: The student develops parry patterns and the ability to parry without yielding ground. Ripostes can include feints, situationally actions on the blade, and renewed attacks if the adversary fails to respond effectively. The transition from defense to offense includes rapid changes in direction facilitated by dynamic footwork.

Counteroffense: The student learns to timethrust in every line, to attack into preparations, to attack into feints, and to read and respond to the adversary’s attempt to seize the weapon and turn that against them.

Phase 3 – Effective use of Skills in Fighting

Strategies and tactics are leveraged to force the adversary out of their preferred mode of fighting into the student’s ideal fight. Probing actions and actions of concealment are leveraged to adapt in real-time to the situation.

Distance: The student learns to use distance traps to rapidly collapse the distance. Examples might include falling back during defensive actions to set a pattern, and then suddenly holding ground or moving forward on a parry. Presenting a series of lunges to establish a distance pattern and then adding an advance lunge or a lunge with a gaining step. They develop the ability to read the space such that they can choose the ideal counterattacking voiding actions for the opponent.

Tempo: Feints may now include tempo traps that take an adversary into more damaging obedience such as a short pause during a feint by disengagement that draws the parry without fully committing to a line. If the adversary is prone to counterattacks, the student may draw counterattacks with the intention of defeating them.

Technique:

Offense: Offense now includes an understanding of the adversary’s likely responses and can dynamically adapt at a tactical level to capitalize on the opponent’s actions.

Defense: The defense includes intentional variety which conceal the student’s patterns such that the opponent cannot easily force the student into obedience. Ripostes can adapt dynamically to the adversary’s defense to establish obedience.

Counteroffense: The student can read tempo well enough to draw a counterattack and defeat it with either a parry-riposte or a counterattack into the counterattack. If the adversary is skilled enough to feint in order to draw a counterattack the student may perceive the feint, and counterattack into it.