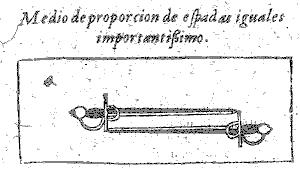

More on the Medio de Proporción…

“To measure the swords is to choose the Medio de Proporción.”

~Carranza

“89. The measure of proportion [Medio de proporción] is to measure the swords or whatever other weapon, and that the tip of the opponent’s sword does not pass the guard of the skilled swordsman.”

~Pacheco

“And thus our author, with very firm examples, proved this point in the illustration of the graduated sword, and the experience for its part has proved it, I do not have to linger on this: I only want to tell you with this our illustration of the long and short sword, the measure that you should choose, if your opponent carries a long one: following in everything the order of the illustration previous to this one, not allowing that in any way the tip of the opponent’s sword passes your guard, for the reasons mentioned before:…”

~Pacheco

These examples of Measuring the swords define the MdP by describing the material and efficient causes. (ie… Material: Of what is the act of finding MdP composed? Two fencers and swords. Efficient cause: How is it done? You measure the extended swords against each other.)

Both of these are practical descriptions of the physical action. It’s very odd in a system which prides itself on demonstrating **why** something should be done.

When Ettenhard defines it, he addresses this conflict by defining MdP using the final cause. (ie… Final cause: What is the intended purpose or goal of the MdP?)

“To choose the Measure of Proportion is to determine a proportionate and convenient distance from which the Swordsman can recognize the movements of his opponent, since for whatever determination of his, there should proceed, of body like of arm and Sword: Of body, by means of footwork: and of Sword, by means of the formation of the Technique.”

~Ettenhard

In my opinion, this is the superior definition because it links the causes together. When these causes appear to come into conflict, (I measured the swords according to the rule but I can’t defend myself), you need to obey the final cause. It would be stupid to measure the swords, be repeatedly struck, and insist you were technically correct when setting your distance.

Pacheco tends to provide rules in sweeping absolutes which can be taken as dogma. Other authors (Ettenhard, Figueriedo) correctly inject some sense into these assertions asking the fencer to use some good sense when reading his work.

Do I have evidence that this understanding of MdP is better for Destreza? I think I do.

Over the length of the tradition we see the simple rule of setting MdP change over time. Why? The swords changed to include cup hilts (material cause: Of what is this composed?). That causes a change in the efficient cause such that the point can now be as close as the pommel instead of the guard (efficient cause: How is this achieved?).

What didn’t change is the final cause (what is the purpose or goal?). That’s what Ettenhard describes and while other parts of the definition changed, they changed to serve the function of the measuring of swords.

It’s not that you cannot be struck, but rather you can recognize the movements forming the attack and effectively defend. That’s the Occam’s Razor of MdP. (In my opinion.)

Beyond that we know that Medio concept is an Aristotelian virtue which strongly suggests that there is more to MdP than just measuring the swords. Aristotelian virtues ask us to choose between two extremes mindfully and choosing well creates beauty. We know that in that case the answer can vary substantially based on the moment-to-moment context and that can be difficult. Being a beautiful fencer means accepting that you are responsible for solving difficult problems in an ever-changing context but when you do it well your will, guided by science, finds a proportionate choice and that choice is beautiful… science and practice leads us to art.