Pointing into Atajo and the Interior Angle

The Tip Leads the Atajo, not the Strong

One of the elements I see as key to the success of the atajo is that we should be leading the atajo with the tip such that the point crosses over the opposing steel first.

“Arriving, then, to the perfect formation of the atajo, it should necessarily consist of three movements, violent, offline lateral [remiss] and natural: with the first the sword that should subject is placed on a superior plane to the other: with the second it is placed transversal over it: and with the other it subjects it…”

~Pacheco

That concept of pointing into the opponent’s weapon is consistent with what the Italians were doing in the late 1500s and early 1600s but it’s different from what we see today in most modern sport fencing schools which are heavily influenced by the French smallsword tradition that developed much later. The French will parry leading the movement with the blade’s strong while the point lags to maintain the point in presence (on target) by bending at the wrist in the lateral plane. That sacrifices defensive power in favor of the faster riposte. Specifically, it does not entirely close the path to target and it exposes the fencer parrying point-in-presence to a forced glide which can be done in a single movement.

French Foil from Ricardo E. Manrique’s Fencing Foil Class Work Illustrated from left to right (p. 22, 21, 19 respectively)

Note that in this image of the engagement the line to the fencers head is still partially open.

What do I mean by a forced glide?

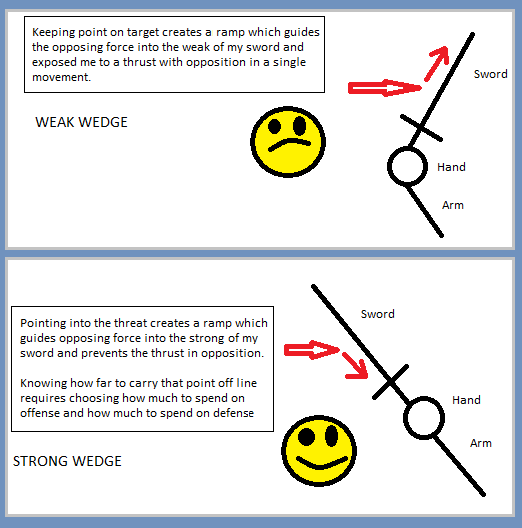

First we need to consider a strong angle versus a weak angle.

When the tip of the parrying weapon is pointed into the threat to lead the parry it creates an inclined plane at the point of engagement. This inclined plane guides resistant and opposing force into the strong of your weapon like a slide or ramp. We might call this a ‘strong angle’ between the swords because it makes you stronger as the adversary pushes into the defense (but it also removes the point from presence meaning your riposte takes longer).

A weak angle between the swords is also an inclined plane but in this case it guides resistant and opposing force into the weak of your weapon like a slide or ramp. The weak angle keeps your point in presence but allows the adversary to change the degrees of strength easily by pressing into your weapon along the sliding surface in a direct path to the target.

Demonstration\Exercise

By that reasoning, a forced glide is a thrust which pushes through the weak angle or engagement. It’s easy to try with a friend to get a sense of what I am talking about. If we know the requirements to form an atajo, can you form an atajo leading with the strong and keeping the point in presence? I don’t think so but we can make a study of this with friends and blades in hand.

Your friend will present the right angle but when you place the atajo your partner will push with a mixed movement lateral and forward into your weapon attempting to bring the point onto target. If you place atajo with the strong angle your partner’s blade will slide along the blade to drop into your strong but if you place the weak angle your partner’s blade slide toward your weak and the adversary becomes stronger in the bind such that your defense will collapse opposed by a single mixed movement.

If that is the demonstration it is the first evidence that the atajo is formed with the point out of presence in a very Carrancine sort of way. We can create a test, we can demonstrate it, and the results are reproducible.

What do the books say?

Is there more evidence? Yes, the authors give us good descriptions.

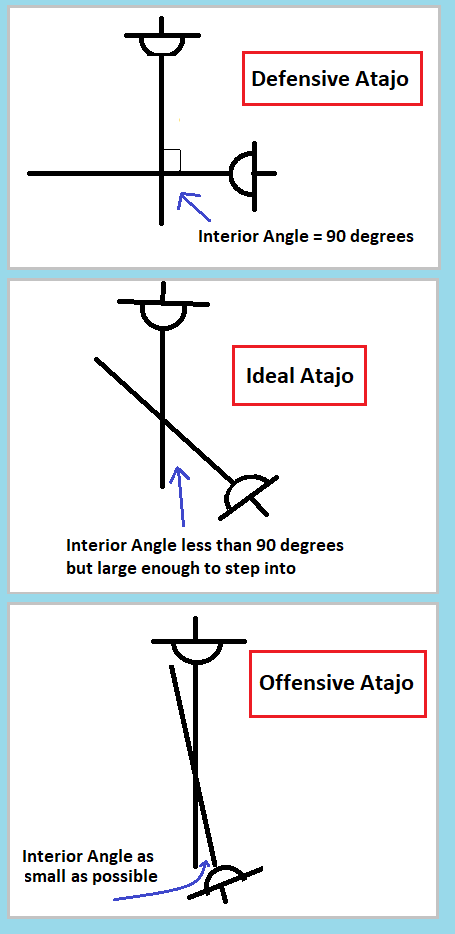

When he describes the atajo in detail Pacheco gives us the requirements, shows us the defensive atajo, the offensive atajo, and then the ideal atajo. The union of these gives us an infinity of possible atajos but that infinite set is bounded by the requirements. If you consider the defensive and offensive atajos as still valid extremes the ideal formation of the atajo seems to become a Medio; a virtuos middle between extremes which is mindfully chosen for best effect.

Defensive

The defensive atajo turns the point into the adversary’s weapon to cross at right angles. It is the most defensive power you can generate and is great for defeating powerful cuts from a heavier sword. The interior angle is 90 degrees.

“…and he will place atajo on the sword cutting it in right angles (as it appears in the demonstration that we put) without it being necessary to communicate too much force for the subjection, because the distance will compensate for this inadvisability: and the imagined line from the toe of his right foot, will also cut in right angles that of the diameter that had been common,…”

~Pacheco

Offensive

The offensive atajo reduces the interior angle as much as possible. That’s a judgment call so how much angle is that? If you look at the requirements, the key requirement here is that the line must be closed and parallel blades do not cross and that cannot close the line. It must be an angle greater than 0 degrees in the interior angle. We know that Pacheco also tells us the thrust that follows will be a mixed movement forward and aligning [reduction] to bring the point back into presence.

“He will have the arm completely extended, without making an angle in the sangradera, and that which he had between him and his body the least acute that he will be able to, so that the violent movement be smaller, when he executes the strike: The hand does not share any extreme of fingernails up or down, it is on edge so that straightly it can receive the strength of the arm, and communicate it, in this way to his sword, like to that sword that he should have subjected: The interior angle that will correspond to him of the swords, be as acute as is possible (given that he should not enter to occupy it with the body) because he has his movement in route, and he can immediately strike with the accidental, or at least it will be almost evident the part of that of reduction that is mixed with it…”

~Pacheco

Most Effective

In the most effective atajo the interior angle is large enough to allow you to step into it and form a conclusion:\

“The interior angle of the swords, is not of more capacity than the width of his body by the depth, so that neither for the inferiority it will be impossible for him to enter in it, nor for the excess of largeness does he quit occupying it, and the movement of conclusion is greater, and for this reason the accidental slower, and the angle that corresponds to the opponent less obtuse: The subjection is made with very intense or reserved strength; so that if the adversary’s sword were missing, making a natural or extraño movement, the extension of the strength does not make the skilled swordsman’s sword lower from that plane where he had placed the atajo, but that he can make a movement of reduction, without another being intermediate for him, or at least the violent being almost imperceptible: And lastly, that the subjected sword, like the subjecting one, does not participate much in the acute angle, with regard to that however much more it is, it will lack the resistant strength in which the agent works, and the arm coming to unite with his body, bringing nearer to the end of the lower rectitude, he will be able to resist less, and the semicircle, that the opponent makes to strike, would be less, and above all it would take from his left hand the reach of the guard that with the compass it would have given him,…”

~Pacheco

With this we have good textual evidence that the point moves first and is directed into the adversary’s weapon to cross it from above which creates the strong angle. In all these examples the point leads the movement into the crossing of the weapons creating an interior angle greater than 0 but equal to or less than 90 degrees, the hand is held fingernails inside (on edge), we obtain equal or better degrees of strength, and we subject with natural power.

Is there evidence that a parry which doesn’t meet these requirements of atajo discussed?

Yes; in 18 contradictions and 100 conclusions we see some of this described.

We are told that there is some common action with bad blade positioning on the outside line which gives the adversary capacity to wound you.

Contradiction 7. “Taking one’s sword by the outside, a common technique and commonly used, has its foundation in a fallacy, that is to separate the sword from the good positioning, giving the adversary plenty of occassion and capacity to wound with the same stab that against him one might form, with bad or good art of defense, remaining without defense and defended.”

~Pacheco

Could this action be a parry with the point maintained on target? Maybe and we see this described in 18 Contradictions as well…

Contradiction 18. “The desvios [deflections], either with single sword or accompanied (case that there is text that approves them) not being united with an attack, or in order to choose a means of common proportion, are of notorious danger due to the power that one gives to the adversary with the methods that produce it, by means of the mixed movement, in order to form an attack with liberty of being able to execute it before they end and at the same time, without being concerned with defense, or doing it and remaining defended.”

~Pacheco

And this:

Conclusion 52. “Following the verdadera destreza and its two known and proper effects, the swordsman can defend himself and not injure, injure and defend himself and, breaking his precepts will be able to whichever procure to injure without defending himself, that are proper effects of the common destreza.”

~Pacheco

We also know that the angles between the swords matters.

Conclusion 63. “For the swordsman’s greater perfection and privation of it that the opponent can have in his techniques, it is convenient for him to open and to close the angles that in his sword are made, superior or inferior or equal; and in this way those that are considered between the two bodies, with which he will deprive the effect of the particular potential and virtue of the medio proporcionado.”

~Pacheco

Is Pacheco talking about strong angle and weak angle here as I described above? I think he is and I think the collection of evidence supports that position.

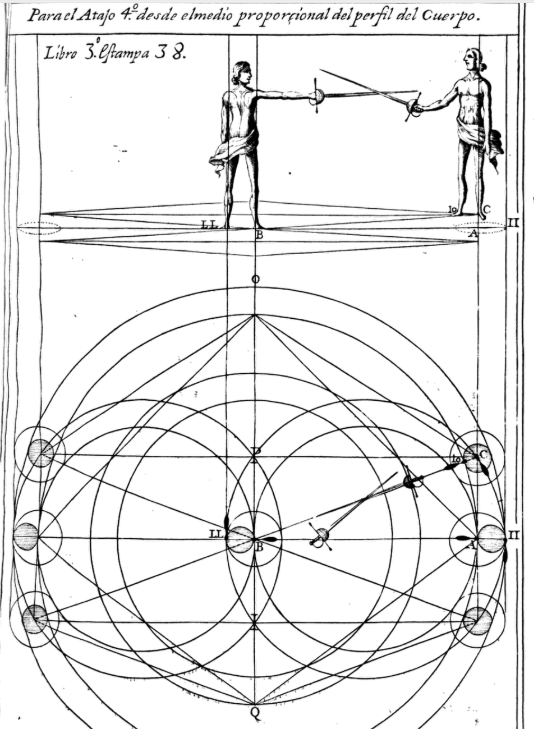

On the other hand do we have evidence of an atajo formed with the point maintained in presence? I’ve looked at Rada’s atajos and the blade shadows cast on the the circle below show the point directed into the opponent’s weapon. When you combine that with the crossing created by lowering the hilt and lifting the tip you create the strong angle. (In atajos 1-4. Atajos 5-8 create the strong angle directing the point into the atajo and then by lowering the tip and lifting the hilt. These knowingly forsake the advantage of natural power.)

I know Rada’s atajos discard some of the Carranza and Pacheco’s requirements but I haven’t seen textual evidence that the strong angle (either from above or below) is no longer correct for Rada.

I readily admit that it may have changed and that would be interesting to find out but I think it would be a mistake to cast Rada’s changes backwards into the older parts of the tradition where the requirements for an atajo seem to be well codified.