In Search of the Rudis

Like many of the stories of my life, this one should start with me being a fool. It was WMAW and assembled there were a collection of instructors trained through Maestro William Gaugler’s fencing program. The Chicago Swordplay Guild wished us to deliver to Maestro Gaugler a gift. Resting inside a carved box was a wooden gladius, a Rudis, of the kind which was traditionally presented to a gladiator who had earned his freedom to become a Rudiarius. Engraved were words expressing their desire that this tradition should persist forever.

At the time I thought it was merely a lovely gesture for his years of hard work but this was a young man’s thinking… it was a fool who could not see the message contained therein which we must all face as fencers, teachers, and members of a martial tradition. What I did not know was that Maestro Gaugler was dying and that his days of servitude to the tradition were ending.

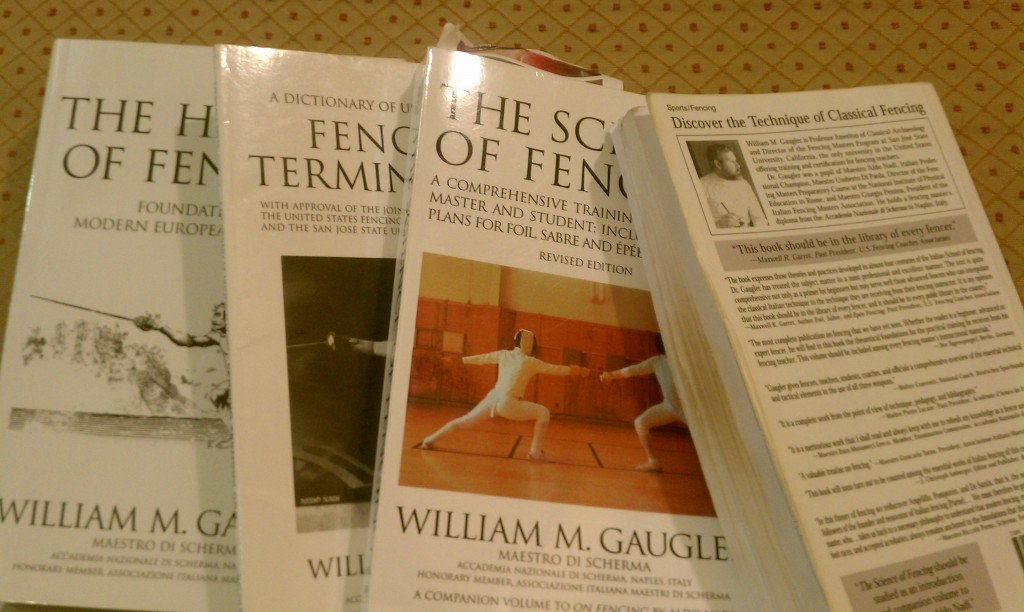

In 1979 Gaugler started the San Jose Fencing Master’s Program which harkened back to an older expression of the tradition in which the inquartata and the passata sotto were still taught. It was taught as if the weapons had greater mass than the trainers themselves actually possessed. The parries emphasized defensive power over the quick ripostes favored in sporting competition. It was a school in which we were required to both percussively strike and then slice in our sabre cuts in order to lay open wounds we would never see. The sabre cuts circled from the elbow to generate enough force to deliver powerful cuts while withdrawing our forearms from the threatened space created when the weapon left the line of offense. It was heavily based on Parise’s work which was itself an attempt to protect the Italian tradition. In order to certify the Fencing Master’s program Gaugler brought masters from Italy to witness the exams and they did so expressing their admiration that he had created so authentically an Italian expression of the art.

Gaugler had created a time capsule waiting for the right moment to be opened. Outside of Gaugler’s Italian time capsule competitive fencing had moved in a different direction but a new movement lay on the horizon and the historical fencing community arrived at the end of the millennium. I had been working on historical traditions for over 10 years before I began studying under the masters that Gaugler had trained. The fencing master’s program was based on a martial system which was well-documented but even more compelling for me was a tradition of teaching which was largely unknown outside the school itself. As I began to train, my own understanding of the historical texts and my ability to transmit the material to students began to accelerate. Not only was my own practice getting better but my ability to train an effective historical Italian fencer had begun to blossom.

The Spanish Destreza author Carranza describes the early rudiments of knowledge as trying to write a letter while knowing only ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’. Having found the Gaugler-trained masters I was awash in a rich language which I had never seen before and I was beginning to write fresh prose as I received the hundreds upon hundreds of touches from my students. Every lesson I gave changed the world in some small way and I was creating fencers who were both powerful fencers but also mastering a systematic way of approaching their martial tradition.

Gaugler’s insistence that lesson be the mirror of combat, that our classwork artificially preserve the mass of actual weapons, had created a clean bridge from the classical tradition into the earlier rapier work and the results were impressive. In my younger days I was a competitor in my fencing. I fought for the love I had of friendly play and the joy of the art itself. Fencing is so often an art form that lasts but for a brief shining moment which transcends all our human imperfections to create an instant of perfect time. What a joy it is to be there and to see the light it brings to the world.

Today I more often work on helping others to kindle their own spark. The day will come when I am held to task for what I did to preserve the traditions in my care. Did I create new and useful work? Did I train new fencers and teachers? Have I done everything in my power to ensure the tradition will persist forever?

I am a thing so well out of his place stumbling and making errors in my work as I strive to rebuild the Iberian traditions and protect the Italian ones. In that sense, being a fool is one of my strengths for I persist in striving regardless of my mistakes in the hope that I can do better. Being publicly wrong and taking the bruises required to correct my fumbling is a cost I will pay if it means the traditions endure. I am a fleeting, temporary thing but I am mindfully working to create a new generation of fencers and teachers who will carry the torch forward. The measure of my worth is not the adversaries I have defeated with my tradition but rather the students and teachers I have given to my tradition.

On December 10, 2011 William Gaugler died. Before the doors were closed on his program it had created 18 masters, 31 provosts, and 47 instructors. His gifted Rudis was a message from a grateful community to the Maestro; it contained a release but also a promise that we would carry his burden going forward so that the art would persist. Your work is done Rudiarius; rest easy.