Italian Rapier Flowchart

(10/12/2009)

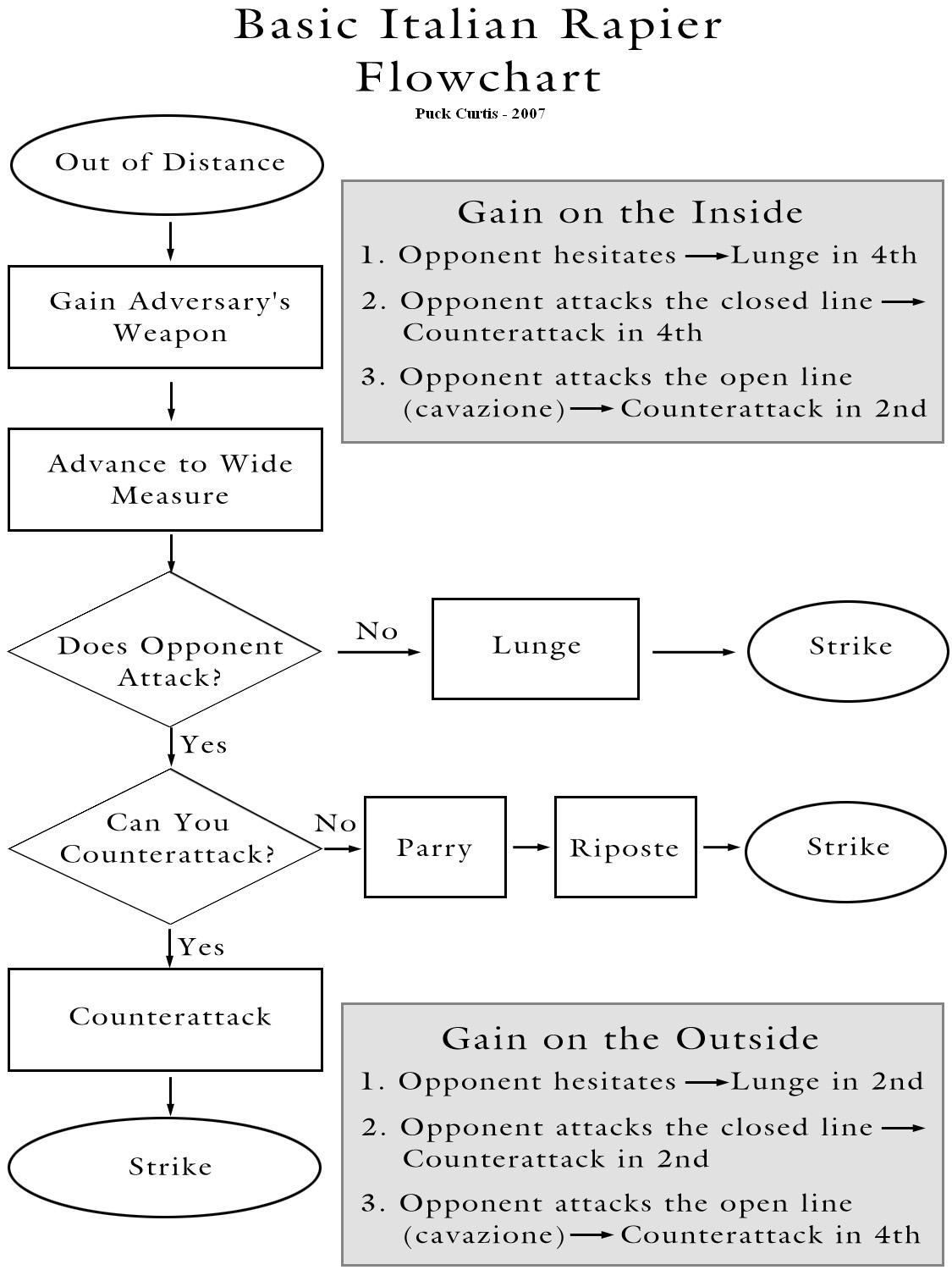

After WMAW 2007 I prepared this Italian rapier flowchart to explain some of the possible actions when executing tactical drills with a student.

There are things I would change about this chart today. This flowchart does not include actions like attacks to the leg, the use of the off hand, and it doesn’t get into detail about execution, but as a basic learning aid I still like it provided the instructor does not limit the instruction solely to this decision tree.

~P.

Hola,

I like the tree. I usually combine the gain and advance to wide measure together since the actions are sequential yet useless if they aren’t combined.

Your tree is right on. It definitely is a good idea for students. I haven’t done a rapier dagger tree yet, but maybe it is something I should do to help give some of my students a more concrete picture of what I’d like to see.

Good job.

By Blayde on October 12, 2009 11:04 pm

Nice. Progression is really clear (to me) at first glance. Would be nice to have more of these for drills when teaching!

Jocelyn (long time lurker on your blog – and you have made me fondly green with envy with what you do!)

By Jocelyn Schreiber on October 13, 2009 12:17 am

Hey Puck,

I like it. For my part, I’ve always used the countertime ladder as the basic tactical decision tree for classical fencing. One needs first and second intentions, of course, but as a model for thinking more than two moves out in an actual fight, it’s clean and logical.

Sean

By Sean Hayes on October 13, 2009 5:51 am

I disagree with the branch where your opponent does not attack you. This chart fails to account for any concept of time. After you advance to wide measure and have gained your opponent’s blade if they do not react then it would be foolish to immediately lunge as you’re moving into a dangerous measure while creating an open time for them to act in (be it by counter-attack or otherwise). You’ve gained control of the blade, but not the time and hence you are not in a safe position to attack. This is true in both rapier and foil.

On your other branch, if this is intended to be a teaching tool for basics, the question “can you counterattack” is too vague. The student needs an indication of something concrete that would allow them to answer that question. In the interest of keeping things simple the two most relevant factors in determining your answer would be “did your opponent attack in the time of your gain/step” and “did your opponent gain control of the blade while attacking.” To keep the same number of nodes currently present, simply replace “can you count-attack” with “did your opponent attack in time and with blade control.” The yes/no responses flow to the opposite responses on your current chart. If you wanted to increase the complexity of the chart, splitting those two questions would allow you greater specificity for the type of counterattack to employ. For a chart this basic it seems reasonable to assume your opponent has the same lunge distance that you do (or knows how to adjust it appropriately), so the question of whether or not their attack is in distance is not needed, but could be added for additional completeness.

Overall, by failing to make any account for time, the chart creates problematic scenarios. Prompting two fencers to follow it at the basic level currently presented will invariably result in numerous “double kills.” A better approach would be to teach the necessary core concepts (time, distance, control of blade, etc.) first so that a more precise chart could be offered to the student before they are taught exercises that, like this one, include multiple decision nodes.

Cheers,

Andrew

By Andrew on October 13, 2009 6:13 am

Looks just like contemporary choice reaction. Some things never change.

By David Charles on October 14, 2009 12:56 am

Hola Joe,

I agree that the two actions are really a sequence but it is important to me that the student cover the line before stepping forward which is why I break it into two states. In execution it will flow forward naturally as you describe.

I haven’t thought about putting together a flowchart for the dagger work yet but I suppose it could be done. Years ago I put together a dui tempi dagger drill that hit all the parries on both sides which might be useful as a form drill.

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 5:56 am

Hola Jocelyn,

I’m pleased that it makes some sense to someone besides me.

:0)

For me this is really the tip of an iceberg and there are so many different directions this could go. It’s not a bad start, but there’s a lot more to play with that isn’t here as well. I just had a wonderful conversation about this chart with Bill Grandy that tweaks it with a more Fabris sensibility which I thought was interesting. I’ll see about putting that chart together and posting it here as well.

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 5:59 am

Hola,

Thanks Maestro. It should look familiar since you asked me to do this in sabre for my Provost exam.

😉

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 6:00 am

Hola Andrew,

We haven’t met so it’s hard for me to know where to start. I realize the chart certainly isn’t exhaustive but it wasn’t meant to be. I like that you’re thinking critically, but I disagree and would like to explain why. If you haven’t spent time with classical Italian fencing before, some of this may seem different to you. I want to address your concerns but it would be helpful if you had access to a copy of Maestro Gaugler’s Science of Fencing which serves as a basis for some of the points below.

Andrew said:

********************

I disagree with the branch where your opponent does not attack you. This chart fails to account for any concept of time. After you advance to wide measure and have gained your opponent’s blade if they do not react then it would be foolish to immediately lunge as you’re moving into a dangerous measure while creating an open time for them to act in (be it by counter-attack or otherwise). You’ve gained control of the blade, but not the time and hence you are not in a safe position to attack. This is true in both rapier and foil.

********************

As M. Hayes recognized, this is the classical Italian countertime ladder applied to Capoferro’s plate 7 (and other plates as well). The fencing actions in this chart are executed in good tempo and it would be a mistake to count tempo by the number of boxes on the chart. Likewise, a tempo can be a measure of motion or a period of stillness which means a hesitation (however short) can also be a tempo. I have already accounted for the adversary’s disengagement in the tempo of the step within the chart.

Attacking when you control the line is perfectly valid fencing. If you are familiar with Maestro Gaugler and Science of Fencing, you can see the beginning of the ladder on pages 96-97 in the foil section on the description of the blade seizure. The blade seizure is “an engagement usually combined with an advance and followed by a straight thrust, glide, or feint. The complete action is comprised of two or more motions.” At least according to M. Gaugler, this sequence (1. blade seizure advance, 2. lunge) is perfectly valid for foil when you use a blade seizure instead of a gain.

The advance into wide measure with the gain and lunge probably won’t seem so odd after you have tried the same sequence from Gaugler’s book with a blade seizure using a foil, sabre, or epee.

One odd thing I noticed with the rapier is that when I sent my students out into the world, their adversaries often didn’t recognize a gained line and would futilely attack into it. This apparent suicide surprised my students which is why I added attacks into the closed line from the unskilled adversary into their tree. It’s bad fencing, but I want my students to correctly strike a suicidal adversary so it found its way into the chart. In classical Italian fencing the engagement completely closes the line so this oddity wouldn’t appear in a tactical tree from the blade seizure.

Andrew Said:

****************

On your other branch, if this is intended to be a teaching tool for basics, the question “can you counterattack” is too vague. The student needs an indication of something concrete that would allow them to answer that question. In the interest of keeping things simple the two most relevant factors in determining your answer would be “did your opponent attack in the time of your gain/step” and “did your opponent gain control of the blade while attacking.” To keep the same number of nodes currently present, simply replace “can you count-attack” with “did your opponent attack in time and with blade control.”

****************

Here, by being more specific you are actually being less precise. Take for example the punta riversa which is a thrust in 4 on the outside line that seeks to sneak around the parry or engagement. The adversary doesn’t control the line but the counterattack is still a losing proposition resulting in at best a double touch. Good judgment will tell you not to timethrust without control of the line. In all cases, this is contextual and good judgment is more valuable than a strict rule.

If you are interested in classical Italian theory, you can see the beginning of the countertime ladder on page 97 of M. Gaugler’s Science when the instructor begins to introduce the occasional tactical disengagement in time to the student’s blade seizure in 4. That disengagement in time is a nice pedagogical tool to keep the student from flying pell-mell from the blade seizure into the rest of the action. From there building up to an arrest in countertime would allow you to make a very similar flowchart to the one I presented above.

Best wishes,

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 7:31 am

Hello Puck,

To address the 2nd topic first, I must respectfully disagree that by being more specific I am being less precise. However, I’m not sure there is a simple way to argue the point sufficiently in a blog post. I would note that, in the context of a simple tree like this one, calling into play atypical actions such as the Punta Reversa is out of place. In the majority of scenarios the questions I posed will be sufficient to determine the appropriate action and provide more insight into the principles behind your choice. Just as the chart is not currently exhaustive of the possible choices, neither does the wording need to account for all possible situations. Relying on “good judgment” is insufficiently precise for a basic exercise. I believe the primary underlying basis for “good judgment” for even an advanced fencer will be the answers to the questions I posed. As such, even though the resulting branch would be less broadly applicable than the current one, it would still cover a more than sufficient portion of the available scenarios while providing more insight to the student.

To next address the first topic, I would make the following notes.

1) As M. Gaugler states on page 114 the blade seizure followed by attack (by straight thrust or glide) comprises two fencing times. However, while you are correct that the hesitation is a time, it is only a single time. As a result, your two-time attack still initiates an additional open time for your opponent to respond in, beyond the initial option of a disengagement in time.

2) Since you solicited constructive feedback from the fencing community at large, and not just the SJSU program, I would be careful of your choice to rely solely on citations of M. Gaugler to make your points. Since you are both Maestri of the same school the citation fails to lend much additional credibility to your points; it would be much like citing a book you wrote yourself. It merely shows you are restating what you were taught (not an invalid thing to do) but does not support an argument that what you were taught is correct or ideal.

3) In the interest of politeness, and since you implied a curiosity regarding my experience with classical Italian fencing, I should note that my original fencing training was under Maestro Sullins not quite a decade ago. I studied primarily classical Italian, 6-10 hours per week, for the first 5 years of my fencing history. In the years since then I have come to disagree with a number of pedagogical elements of the system as presented by Gaugler. In this case, the element of disagreement is the teaching of complex actions and decisions prior to fundamental principles. I believe a strong fencing pedagogy should emphasize that all first intention attacks should be attacks in time (as described by M. Gaugler on page 122, nearly 100 pages too late as all the necessary elements to teach attacks in time are covered before page 30). Second intention attacks and actions in countertime can be initiated either with or without a time as the open time generated by your first intention actions should generate a time to use in your continuation.

Now, it would be fair for you to point out that I have offered no authority beyond my own in making the above assertions. However, I also know you have stated in the past that Maestri are not infallible, and they are by and large the most significant authorities we have on these subjects. As a result, I can cite for you no authority that would overrule the book you’ve referenced, and I do not disagree that your chart is in line with the teachings of that book. Where appropriate, I have attempted to provide references to sections of that same book that I believe support my assertions and suggest they are not contradictory to the tradition you were trained in. Since pure citation is insufficient to address our disagreement, I would challenge you to present an argument supporting one and/or all of the following points (which I believe are implied or stated in your previous posts):

1) Attacks out of time are as good as (or better than) attacks in time.

On this item, if you believe attacks in time are better than attacks out of time, you have no basis to disagree with my initial comment about your first branch unless you present an argument for item 2 below.

2) It is pedagogically more effective to teach complex actions and exercises with decision points prior to teaching simple attacks in time.

3) The principles of time and blade control are not a significant portion of the basis for good fencing judgment to determine a choice among basic actions.

On this item, I welcome a presentation of what principles good fencing judgment is comprised of (in general or in the specific situation presented) if not the above.

I look forward to your response.

Cheers,

Andrew

By Andrew Telesca on October 14, 2009 9:30 am

Sorry to jump in so late, but I thought I’d add a little to this discussion–or rather, I’ll let Marcelli add to it. The chart fits Marcelli’s instructions pretty much to the letter. Marcelli wants you to engage your opponent from out of measure and then (immediately, i.e. as part of one contiguous motion) step into measure. His instructions are that if your opponent performs a cavazione then you are to attack through it. However, if your opponent does not move, then he tells us to immediately attack. That is, engage, enter, then attack. Thus, we can summarize Marcelli’s instructions as being:

1. Engage and enter

2a. Opponent stands still or performs cavazione: attack

2b. Opponent attacks: counterattack.

2c. Opponent retreats: start over at 1.

Note that in this case, neither Puck nor Marcelli are ranking these actions. I’m sure Puck has a preferred hierarchy, and Marcelli definitely does (he tells us that would prefer to strike with a counterattack, but that is in a different section)

By Steven Reich on October 14, 2009 6:29 pm

Andrew Said:

**************************

To address the 2nd topic first, I must respectfully disagree that by being more specific I am being less precise. However, I’m not sure there is a simple way to argue the point sufficiently in a blog post. I would note that, in the context of a simple tree like this one, calling into play atypical actions such as the Punta Reversa is out of place. In the majority of scenarios the questions I posed will be sufficient to determine the appropriate action and provide more insight into the principles behind your choice. Just as the chart is not currently exhaustive of the possible choices, neither does the wording need to account for all possible situations. Relying on “good judgment” is insufficiently precise for a basic exercise. I believe the primary underlying basis for “good judgment” for even an advanced fencer will be the answers to the questions I posed. As such, even though the resulting branch would be less broadly applicable than the current one, it would still cover a more than sufficient portion of the available scenarios while providing more insight to the student.

**************************

I don’t have a problem with you disagreeing, but if students can’t recognize a suicidal adversary they will continually get hit trying to counterattack. A tall fencer with a long blade trying to hook around engagement or parry to strike is terribly common in amateur rapier especially when blade lengths are so often mismatched. A punta riversa is only one manifestation which is a convenient example.

If you have an issue with the phrase ‘good judgment’ then consider replacing that with an understanding of the theory and using it correctly in context.

***************************

1) As M. Gaugler states on page 114 the blade seizure followed by attack (by straight thrust or glide) comprises two fencing times. However, while you are correct that the hesitation is a time, it is only a single time. As a result, your two-time attack still initiates an additional open time for your opponent to respond in, beyond the initial option of a disengagement in time.

***************************

Two times is two times. Not much to dispute there. The issue you seem to be pressing is that simple attacks are invalid unless they always take place in the adversary’s tempo. I disagree.

Any discussion of tempo must by nature be qualitative. Gaugler defines time as “the favorable moment an offensive action will catch the adversary off guard.” There is a large body of historical texts describing the same kind of favorable moment to deliver an attack and the adversary generating a tempo is only one part of that. More to the point, simple attacks work in this manner on a regular basis which means a fencing teacher disregards the theory at their own peril (or rather the peril of their students). Without simple attacks the student runs the risk of becoming a punching bag as they stand in wide measure waiting.

I have demonstrated that it exists in theory which you initially disputed. If we follow your logic down the trail a bit, changes of engagement, transports, envelopments, beats, blade cover, and disarmaments are equally invalid. Further, drawing a parry for a feint is predicated on the ability to hit with a simple attack which may or may not be in tempo. If you consider Fabris plate 22, (p.56) you will see exactly this sort of feint executed in order to draw a parry. That feint should have to potential to become an assault if the adversary fails to address it. Without some form of simple attack the student must risk being continually in obedience to an adversary.

****************************

2) Since you solicited constructive feedback from the fencing community at large, and not just the SJSU program, I would be careful of your choice to rely solely on citations of M. Gaugler to make your points. Since you are both Maestri of the same school the citation fails to lend much additional credibility to your points; it would be much like citing a book you wrote yourself. It merely shows you are restating what you were taught (not an invalid thing to do) but does not support an argument that what you were taught is correct or ideal.

****************************

My intention in citing Gaugler was to point you to a commonly accepted body of classical theory that demonstrates that the sequence is valid with a foil (which you disputed). You don’t have to accept M. Gaugler as an authority and his work doesn’t need me to defend it.

****************************

3) In the interest of politeness, and since you implied a curiosity regarding my experience with classical Italian fencing, I should note that my original fencing training was under Maestro Sullins not quite a decade ago. I studied primarily classical Italian, 6-10 hours per week, for the first 5 years of my fencing history. In the years since then I have come to disagree with a number of pedagogical elements of the system as presented by Gaugler. In this case, the element of disagreement is the teaching of complex actions and decisions prior to fundamental principles. I believe a strong fencing pedagogy should emphasize that all first intention attacks should be attacks in time (as described by M. Gaugler on page 122, nearly 100 pages too late as all the necessary elements to teach attacks in time are covered before page 30). Second intention attacks and actions in countertime can be initiated either with or without a time as the open time generated by your first intention actions should generate a time to use in your continuation.

****************************

I think you left politeness by the wayside awhile back Andrew. If you have trained with M. Sullins, you have been at least exposed to the tradition. If it doesn’t meet your needs I’m certainly not going to force it on you.

****************************

Now, it would be fair for you to point out that I have offered no authority beyond my own in making the above assertions. However, I also know you have stated in the past that Maestri are not infallible, and they are by and large the most significant authorities we have on these subjects. As a result, I can cite for you no authority that would overrule the book you’ve referenced, and I do not disagree that your chart is in line with the teachings of that book. Where appropriate, I have attempted to provide references to sections of that same book that I believe support my assertions and suggest they are not contradictory to the tradition you were trained in. Since pure citation is insufficient to address our disagreement, I would challenge you to present an argument supporting one and/or all of the following points (which I believe are implied or stated in your previous posts):

****************************

You haven’t really provided a cited argument so much as argued against the source you cited.

*****************************

1) Attacks out of time are as good as (or better than) attacks in time.

*****************************

You have created a convenient strawman argument which is more convenient than my actual position. Actions executed in the adversary’s tempo are better, but there is nothing inherently wrong with a well-executed simple attack and the blade seizure and glide is one example of that.

As best I can tell you assert that simple attacks are invalid without a tempo from the adversary. It isn’t a stretch to create an equally silly strawman in which we could come on guard and stare at each other waiting for a tempo until we both collapse. (I suppose the first person to collapse generates the tempo you are waiting for.)

Simple attacks form one part of a technical foundation for the tradition. Unless you teach them in time on the first day, the technical lesson comes first.

*****************************

2) It is pedagogically more effective to teach complex actions and exercises with decision points prior to teaching simple attacks in time.

*****************************

Again, you are creating a strawman argument here. You are making assertions about how I teach my students without any information to support it. The flowchart doesn’t represent a technical lesson but instead some possible progressions.

*****************************

3) The principles of time and blade control are not a significant portion of the basis for good fencing judgment to determine a choice among basic actions.

*****************************

This is another strawman which is so strained as to be ridiculous. If your argument is that a flowchart is a poor substitution for a book on fencing or a teacher with blade in hand at least in that, we agree. The goal of teaching is to produce a fencer whose good judgment is manifested through form, timing, control of measure, and execution.

In order for your critical feedback to be anything but polemic, it should also be persuasive beyond your own assertion that you are correct. While there is some merit to making the statement that attacks in the adversary’s tempo are best, tossing the simple attacks by the wayside is a mistake which is not supported by theory or practice.

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 6:53 pm

Hi, all. Glad to be here.

A glide from engagement is one of the most basic actions in Italian rapier. It happens in every author from Fabris to Giganti to Capoferro (who has a whole chapter on “ferire secondo il punto”) to the later Baroque masters such as Marcelli and Di Mazo. I’ll be glad to provide quotes–please tell me how many constitute “normalcy” in your book.

After you engage, if the opponent does not respond, you either strike with a glide or feint. And to be even more precise, even a feint is nothing but a glide that the opponent tries to parry–at least as defined by the early-17th C masters.

Tom

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 6:58 pm

“If the opponent stands motionless in guard and waits, and you advance into measure and immediately deliver your attack in his opening, this is a tempo”

Giganti

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:04 pm

“Lastly, if the opponent does not perform the cavazione, advance into measure while maintaining possession of his blade, and immediately attack his opening with a thrust; then, recover out of measure placing your blade lightly over his.’

Giganti

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:05 pm

“You can gain the opponent’s sword […] without changing guard while you advance, so that you can then strike him to the outside above his sword, or, if he performs a cavazione, below it.”

Fabris

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:14 pm

“Striking the opponent can happen in three situations: when I am stationary and he moves to find the measure, *when he is stationary and I seek the measure,* or when we both move to seek the measure.”

“Striking through the point: when the opponent’s point is in your presence, you can strike in straight line at the height of the opponent’s point, seizing a few inches of the point of his weapon with your forte.”

Capoferro

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:31 pm

“The Gentleman N. 12 let his opponent gain his sword and advance in perfect measure […]. At that point, the opponent can strike in many ways:

1) With a seconda to the face, either right after gaining the sword or after his adversary’s cavazione.”

Alfieri

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:48 pm

“You can either strike in tempo–meaning during any movement of the opponent’s sword, or parrying his attack and striking at the same time. Or, you can strike before the tempo, meaning striking resolutely while your opponent is motionless with his sword, feet or body.”

Pallavicini

By Tom Leoni on October 14, 2009 7:55 pm

Hello all,

First, Steve’s Marcelli feedback brings up another obvious option which is easy to add to the flowchart. If the adversary retreats, start over again. Very nice and something we included in tactical lessons even if I forgot to put it into the chart.

Bill Grandy offered some excellent critical feedback about seeking misura stretta and I have asked his permission to include it here:

Bill said:

***********************************

Hi Puck, good chart! If I may add a bit of constructive criticism, in general one should not attack from misura larga when the line is closed but your opponent does nothing, based on the sources. If your opponent attacks, you should seek the misura stretta, because that is the measure in which you can make an attack out of tempo (provided you keep the line covered). At the misura larga, you really should only attack in tempo. Just food for thought!

***********************************

Puck replies:

***********************************

Constructive criticism is good! I want to make certain you understand what I mean and then we can discuss it.

The root action is the skilled fencer gaining the line, moving into measure and striking with a lunge.

A. In the tempo of the step, the adversary may hesitate which triggers our lunge.

B. In the tempo of the step, the adversary may attack with a cavazione in time which triggers the counterattack (or a parry-riposte).

Initially, these were the 2 options I taught. When my students were free fencing outside the school I noticed their adversaries didn’t recognize the line was closed and some were attacking futilely into the gained line. At that point I added option C.

C. In the tempo of the step, the unskilled fencer may attack the closed line, triggering a counterattack (or parry-riposte).

Thoughts?

***********************************

Bill said:

***********************************

I realized I made a typo earlier. I meant “If your opponent *doesn’t* attack, you should seek the misura stretta…”, which seems to be advised more often than not in the sources. So I don’t feel option A should be a “standard” option for this scenario, even if it isn’t necessarily a wrong option. If one steps into measure with the line closed, and the opponent does nothing, its more ideal to either seek the narrow measure (where you don’t have to wait for a tempo to attack), or provoke a tempo.

***********************************

Puck replies:

***********************************

I’m with you now. Do you mind if I copy your thoughts into the ‘Comments’ section of the blog? (I like a well reasoned discussion and you make good points.)

As to seeking the misura stretta, I agree that it is an option that doesn’t show up in the flowchart (along with many others) but my concern would be that after you have taken one tempo to enter wide measure you are taking another to move into close measure. Because the student has to be ready to respond in each tempo I consider this more nuanced and advanced.

We could flowchart your version by putting the same decisions into the flowchart on the tempo of each step. Not bad fencing, but more difficult I think.

***********************************

Bill said:

***********************************

Sure, you can put that in the comments! My concern about making option “A” a standard is that it is an attack out of tempo. Coming from a Fabris point of view, I can’t think of a single time that he ever advises this (though he counters it). I don’t recall Alfieri, Giganti or Capoferro ever advising this, either, though I spend a lot less time with those texts. On the flip side, they all tell you to seek the misura stretta, and Fabris is the one who flat out says that once you are there you don’t even have to attack in tempo if you don’t want (though there’s the implication that it still isn’t a bad idea).

To be clear, I’m not saying attacking from misura larga after you’ve gained the sword is necessarily wrong. I’m just not sure if it should be one of the main options.

***********************************

Puck Replies:

***********************************

You are absolutely correct about the advice Fabris gives. I think the difference here is our source material. Fabris also tells us that if “you want to gain the misura stretta while the opponent is in his guard, the danger is considerable.” (p.7)

You get safely into misura stretta with a **counter-posture**. A gain (or finding the sword) is similar to a counter-posture but while the counter-posture closes completely the gain doesn’t close the line but rather covers it. (p.15)

Capoferro seems to address counter-posture directly in his text:

“73. They who like the guards, and counterguards, and stringering here, there, above, and below, the feints, and counterfeints, the diagonal paces, the voids of the legs, and the crossings, necessarily form and move their bodies in many strange ways; which, as things done by chance and that were founded in no reasons that were sound and true, we will leave to their authors.”

~Swanger and Wilson’s Capoferro

This seems to be pointed directly at Fabris. If Capoferro is only using the gain, it would be dangerous to seek misura stretta.

Fabris does indicate that the lunge is one of the most commonly used attacks (p.22) which indicates it has a place. The question then becomes, “Why would our fencer feint in plate 22 (p.56)?” My reading is that the feint presents an opportunity to either react to the parry or if the adversary does nothing to strike with a straight lunge. (I think feints should have the promise of violence if not addressed.)

I don’t disagree so much as I wish to explain and hear your thoughts? Would you mind if I put together another flowchart with your recommendations included?

***********************************

Bill said:

***********************************

I’d never put the connection between that Capoferro quote being pointed at Fabris. Interesting!

Regarding your point about plate 22: I didn’t mean to imply that attacking from misura larga was necessarily wrong, but that it doesn’t appear to be the norm. You’re absolutely correct that a feint should have the ability to be a real threat (that’s the best way to make the feint believable, IMO). But attacking out of tempo is much more of the exception in Italian rapier(at least, in the late 16th and early 17th c.), and even Fabris himself points out that the inherent flaw in a feint is that you have to make a tempo in order to provoke one. So I would still argue that lunging from misura larga makes more sense when there is a tempo to exploit, and that seems to be the norm in the treatises. If there is no tempo, lunging from misura stretta is not only safer (assuming the line is closed as you proceed), but also means that the opponent has very little time to defend, and even if that opponent retreats then he/she will still be in measure and will be hit.

But of course, I realize your goal is to make a nice concise and easy to follow flow chart as a teaching tool, not to make a convoluted and confusing mess! My only nitpick (and it is definitely a nitpick!) is that the flow chart implies that lunging out of tempo is the normal response, and I’m not so sure I agree with that particular bit.

*************************************

Thanks for the feedback thus far and I’ll create an updated flowchart in the future.

~P.

By puck on October 14, 2009 9:34 pm

Hello Puck,

I am sorry you find my attempts to provide the requested feedback impolite, and consider my interpretations of your positions to be “straw men.” Unfortunately, in your responses to my commentary the items I was attempting to address have been stretched far too thin and the space filled with numerous concepts outside of relevance. It would be unreasonable to take the time and try to address them in this format. I will address a single point that I believe is the most relevant, and I hope we can leave things there.

You have construed my argument to be that the simple attack out of time — and by extension any action out of time — is invalid. Any fencer would recognize this as a ridiculous position; it is insulting that you would think my position so naive. As it relates to your tree, my point is as follows.

In the branch where your opponent hesitates on your coming into measure a neutral position has been created in time, and you hold an advantage of blade control. In order to proceed safely, a favorable time must be generated, because we all know that if we attack blindly at this point our opponent has an opportunity to respond that is equal to our attack. To follow the tree from the lunge to the hit without accounting for this opportunity to respond is not valid. This does not mean the simple attack is invalid. However, to ensure our safety in our attack, time must be accounted for. This can be done either by generating a time from your opponent prior to executing the simple attack (now the simple attack in time) or by preparing to continue from the simple attack out of time (which we can agree should fail against a skilled fencer) in second intention. If by luck, or a lack of skill in our opponent, the simple attack out of time lands without needing to continue in second intention, then we continue as Giganti suggests in Tom’s post above and immediately recover and we constrain ourselves to not be distracted by our good fortune. The third (and I believe last) situation of the valid simple attack is the one you presented as follows:

“If you consider Fabris plate 22, (p.56) you will see exactly this sort of feint executed in order to draw a parry. That feint should have to potential to become an assault if the adversary fails to address it. ”

Put another way, prior to the lunge we extend (as always) and, since we have the line, if our opponent hesitates, we have now gained a time to continue with the lunge, so long as it is fluid and immediately follows from the extension. This additional hesitation on the extension cannot be confused with the hesitation on the advance into measure and it is this additional hesitation that generates the 2nd time necessary to make the simple attack in safety. If this is the situation you wished to account for in your flow chart, then an additional node accounting for your opponent’s hesitation is needed prior to the “strike” node. This same node, when branched to the direction where your opponent does not hesitate, accounts for the time you have given him to act in and leads to a more complex interaction. My original point, now long obscured, was merely that this additional node is needed for the flow chart to be accurate, even if the branch where your opponent does not hesitate is negated for simplicity.

Regarding the preference I expressed, my personal and pedagogical preference is to place this additional node prior to the lunge rather than after, indicating that we gain a time before executing the simple attack, as I believe this requires less discernment for the beginner than determining the truth of your opponent’s hesitation on the extension. For the advanced fencer against a skilled opponent who would not hesitate, the interaction necessary to gain a time prior to the lunge creates the complexity that would otherwise occur after the lunge when your opponent uses that time, but it does so at a safer distance.

I hope that clears things up.

Cheers,

Andrew

By Andrew Telesca on October 14, 2009 9:56 pm

Andrew, I’m coming late into this discussion, and I’m trying to understand your argument.

You said in your first post: “After you advance to wide measure and have gained your opponent’s blade if they do not react then it would be foolish to immediately lunge as you’re moving into a dangerous measure while creating an open time for them to act in (be it by counter-attack or otherwise). You’ve gained control of the blade, but not the time and hence you are not in a safe position to attack. This is true in both rapier and foil.”

And then in your most recent post: “You have construed my argument to be that the simple attack out of time — and by extension any action out of time — is invalid. Any fencer would recognize this as a ridiculous position; it is insulting that you would think my position so naive.”

Could you give an example of a simple attack done out of time that is valid? A compound attack that doesn’t use feints?

Also, Tom and Steve have demonstrated pretty clearly from the historical manuals that a lunge after the gain is squarely within the written Italian rapier tradition. How do you square your position within this tradition?

By Kevin Murakoshi on October 14, 2009 11:19 pm

Andrew, I think I see your point as being this.

You said: “This does not mean the simple attack is invalid. However, to ensure our safety in our attack, time must be accounted for. This can be done either by generating a time from your opponent prior to executing the simple attack (now the simple attack in time) or by preparing to continue from the simple attack out of time (which we can agree should fail against a skilled fencer) in second intention.”

The problem I see with this–strictly in the tradition of 17th Century Italian rapier–is that as long as you have secured the opponent’s blade, a simple attack is perfectly considered within the canons of the art. Depending on the author you consult, they may even call it an attack in tempo (e.g. Giganti listing this explicitly in his discussion of tempo), since tempo is also the measurement of stillness against motion, not only of motion against (or between instances of) stillness.

Also, let’s remember that even the strictest notions of tempo are actually pedagogical devices–we are not talking the law of gravity, but reasonable ways to ensure that attacks succeed safely. Put in the simplest possible terms, as long as you can’t attack me in the line we’re using (because I’ve found your sword), if I attack you quickly and strongly, you receive the hit.

Incidentally, these are not my words, but Giganti’s and Marcelli’s.

In yet another way to put this, I think your points are valid in theory, but you are treating what are rules of an art (i.e. pedagogical devices) as immutable laws of science. The Masters themselves exemplify the fact that after you find the opponent’s sword, you basically have three choices (in no particular priority):

1 – Perform an attack while retaining the advantage of the sword (i.e. glide or transport)

2 – Perform a feint under the same conditions as 1

3 – Wait for the opponent to launch an attack, give a tempo or change his guard

Each of these is equally admissible under the rules of the art, with plenty of historical documentation to support it. Yours are good points, but you are taking a bit of a Platonic view of an art that was fundamentally pragmatic and relied more on tradition than adherence to a perfect model.

Tom

By Tom Leoni on October 15, 2009 2:18 am

Kevin, Tom, thank you for the replies, they are well considered, so let me try and provide some additional thoughts.

Kevin,

I give two examples of such simple attacks in my previous post. The first is the simeple attack out of time in preparation for the 2nd intention attack. This accounts for the fact that the simple attack out of time leaves your opponent an opportunity to respond so your plan needs to account for that time with a prepared continuation. The 2nd is the case offered where one has sufficient awareness to determine an additional hesitation on the part of your opponent (most likely during your extension) seperate from the hesitation the chart shows when coming into distance. One could argue that this is actually in time, but it is certainly a grey area. The subset of this when your opponent makes a mistake in the distance is probably the most often case of it being seen as effective in practice since a shorter hesitation is needed, but that is outside the model of the flow chart. The part of Puck’s statement that I was responding to as particularly ridiculous was the choice to extend my statement to imply that all actions done out of time are invalid. This is foolish and I suspect that is evident to anyone reading.

As to squaring it with the tradition, that requires a lot more work than I can put into a blog post right now (my apologies for this). The concepts here are sufficiently complex that simple quotes as I see typically used would not be sufficient, instead you have to reconstruct the actual arguments used in the masters’ discussions of both actions and time and the movement from the possible to the ideal. The key factor that I believe you want to consider was my statement that “In order to proceed safely, a favorable time must be generated, because we all know that if we attack blindly at this point our opponent has an opportunity to respond that is equal to our attack.” (okay, not qutie equal since we do control a line, but equal in time with an opportunity to change the line, so it is a minor advantage) While I agree the masters give examples of attacks done as described, it is always with consideration in place for the opponent’s opportunity to respond. I understand that this response will likely be considered insufficient to make a point in the general discourse method of these online discussions; the medium is unfortunately far from ideal, which is why I rarely post anything online.

Tom,

Thank you for the very reasonable post. I’m not sure I can respond to it adaquately here, though I’d be more than happy to discuss it at length over drinks in February. Let me make a few notes that I hope will be helpful.

First, in going back and re-reading Puck’s original blog post, I’ve noticed that I have been making an assumption that I should have made explicit. In the e-mail Puck sent out about this post he claimed it was equally valid in both rapier and the classical weapons, so I have been attempting to keep concepts at a high level that is equally valid for both. I now realize that the text of the post iteself does not make that claim and only applies to the rapier, which would change the way I would phrase some of my previous statements, though I believe they are still valid.

That said, I hope it clears up some of your disagreement over the pragmatic vs. theory issue. The pragmatic application will change some for classical vs. rapier, to retain applicability to both I had to stick with a pure theory standpoint. However, given that we are discussing a pedagogical tool (the flow chart) I would still claim it should fit with the theoretical model.

I would agree that in some cases the simple attack while retaining the sword can end up being in time due to the hesitation (this is a grey area as I mentioned to Kevin). I find this less advantageous than attacking while your opponent is in motion, but the difference in the weapons certainly makes it more viable in rapier than in foil. However, even in rapier, controlling only the blade is not sufficient to make the touch safely. What it serves to do is reduce the chance that your opponent can successfully counter attack, which gives you an opportunity to either get back out safely or continue on his defense. If you want to give yourself the best odds of the safe hit in first intention, you need to control the distance and tempo as well. Doing this also restricts your opponent’s reactions (and ability to change the line) and makes it easier to continue if he does defend. Im most cases, if I cannot manipulate the opponent to give me your option (3) in most instances I would prefer to launch a false attack (which I would say should be option (1.5) as it is not on your list and has elements of both 1 and 2) rather than make the option (1) attack. But I agree they are all viable options, so long as you retain an understanding of the potentially consequences and are ready to respond to them.

Now, how large of a gap should there be between practice and theory? That’s an item for the debate over drinks. I believe there are numerous elements in the texts suggesting the masters often took a Platonic view of the art and developed it based on science and geometry rather than purely tradition. The closer you come to fencing based on the theoretical model, the more effective (and hence pragmatic) your fencing becomes. To strive for less is to rely on luck.

We should really find time to do some fencing. In all the times we’ve met I don’t think we’ve actually fenced any yet, which is a shame.

Gosh, these are long posts. Now I’m remembering why I try not to get into these discussions online, I’d really much rather spend this fencing. I’m going to have to make this my last post on the subject, but I hope the thoughts have been useful to some of you. Thank you all for your responses; they have provided me an excellent opportunity to refine the way I express some of these concepts. I’ll try to stop back again in the next day or two and read any additional responses to this post.

Cheers,

Andrew

By Andrew Telesca on October 15, 2009 6:56 pm

Hey, Andrew, thanks for the post.

I agree that for some masters, as you say, the closer you come to fencing based on the theoretical model, the more effective you become. For others like Fabris, once you internalize the essence of the art (i.e. strongs and weaks, open and closed lines and measure–he tellingly leaves out tempo), you can step out of the pedagogical canons and “go as you please,” to use his words. 🙂

The progression, as I have bought into it for myself, goes something like this: 1) use the art and its rules as “teacups” from which the teachings of the art can go most effectively from an instructor (or book when this is unavailable) to me; then, 2) bear in mind that it’s the liquid (i.e. the essence of the discipline) that is being passed on, not the teacup itself–although the teacup becomes itself an historical artifact worth of a lifetime of study, especially in case of the historical martial arts.

Interesting discussion. Agreed on the drinks and the fencing!

Tom

By Tom Leoni on October 15, 2009 7:59 pm

Hi Andrew,

First off, tanks for clearing that up for me, it makes discussions on your points easier without the personal attacks. I am afraid, however, that I disagree with you on a number of points.

Considering your two examples you give for valid simple attacks out of tempo.

1) The simple attack used to begin the second intention.

While I can see your idea about drawing the second intention. The reality is that second intention actions are predicated on the ability to hit with a first intention action. Thus, the first intention action must be a reasonable threat. Puck’s chart does not progress beyond any first intention actions, a more complicated tree may rely on this attack to create a second intention situation (or compound attack).

2) The hesitation upon entering measure.

You suggest that a node be added anticipating the hesitation of the opponent upon the fencer’s entering measure. I disagree with the need for this node for two reasons.

First, the additional node (and necessarily any nodes after it) is superfluous. Any decisions made after the hesitation can be accurately modeled on the earlier nodes (counter-attack in the closed line, or counter-attack in the open line). Whether the opponent chooses to attack in the first tempo of the foot, or out of tempo (after the step), the counter-actions used are identical. Thus, adding the extra node is unnecessary.

Second, I worry that the addition of a new choice node at this stage would encourage beginning fencers to wait to perceive their opponent’s hesitation. This in turn would create a new tempo (the attacker’s stillness) which opens them up to another attack in time.

By Kevin Murakoshi on October 15, 2009 9:25 pm

–Looking at the conversation as a whole, I can see that a more complicated flowchart might be an interesting project.

I don’t think removing the lunge from wide measure with the gain is warranted as Tom and Steve’s excellent citations make it clear that this is definitely part of the canonical tradition.

~P.

By puck on October 16, 2009 10:49 pm

Canonical? What do you me… oh, nevermind. 🙂

By Tom Leoni on October 16, 2009 11:24 pm

Speaking as a programmer, I detest flowcharts; it’s not how I work (and I’m pretty sure Paul Graham would agree). This one I like, though, because it’s how we practice. (My instructor has recently been stressing: Find opponent’s weapon and advance to wide measure. Does opponent attack? No. Attack. Why? Because he’s noticed that all too often people “hang out” in wide measure, waiting for something to happen, and he wants to promote decisiveness, taking the initiative. These are drills, after all). But should it become more complicated … rather than some complicated flowchart that only an IBM mainframe programmer could understand, I’m wondering whether something more atomic, more Turing machine-like, might not be worth thinking about. In other words, suppose I’m some dumb fencing cluck who doesn’t want to die: can you give me, not some master plan, but some very discrete scenarios that I can put together to make a fight (not a drill: putting together a drill is another matter entirely; I want to put together a fight from iddy-bitty building blocks that make martial sense). I’m not a Garry Kasparov, in other words; I’m a Joe Blow who’s smart enough to want to stay alive. Perhaps a series of discrete flowcharts such as these, rather than a more complicated one, might be in order. Then I can link them together in the fight as the fight develops.

Perhaps of some relevance is this. On Wednesday night I found myself halfway through a movement of conclusion without realizing it. When I realized it, I said, H… Cr.p–this is a movement of conclusion! Only then did I think, this is how I’ve seen Puck continue from this point, and so I did, to the general approbation of the onlookers. Nice feeling, when you’re in the midst of something (and you got yourself there logically and naturally), _then_ you recognize the pattern, _then_ you use the pattern to finish. The pattern, though, is something very discrete. I hope this makes some sense.

By Charles Blair on October 17, 2009 3:04 am

Hola Charles,

I think that is an interesting suggestion and very workable. It would be even better as an interactive web-based chart with links to the different individual charts.

I’m afraid you are going to have to give more detail on which conclusion you managed to do. You can’t tease us with a hint of violence and not provide us with the details.

😀

By puck on October 20, 2009 12:05 am

Thanks, Puck, for your response.

The movement I performed in this instance is the one ending in a cut to the head. I believe we drilled it at WMAW 2009, and I believe I saw you perform it at the Feast against my instructor, John O’Meara. (I virtually cringed when I saw it, actually, because I don’t think poor John was expecting it.) I’ve also performed movements of conclusion that included thrusts in place of the cut.

If I understand Carranza correctly (in principle–I’m not saying he actually says this), a movement of conclusion might legitimately end simply in a threat, since he says (and I’m paraphrasing from memory), that La Verdadera Destreza doesn’t teach one to kill, but only how to kill: there may be situations in which the Christian response would be to threaten death, leaving it up to the opponent whether to choose death, or not.

My point here, though, is that in the fight I saw something that triggered a recollection. What I recollected was a pattern that had a beginning, a middle, and an end. What I saw was the beginning. When I saw that, I began enacting the pattern, embodying it, following it through to its (pretty much predictable) conclusion.

I’ve done this before. Pallavicini describes a play in his 1670 playbook which I found very interesting for a number of reasons. I analyzed it (decomposed it into its constituent parts, as opposed to composing it from constituent parts), tested the parts for correctness given the Italian rapier theory I’d been taught, reassured myself that each part could be defended theoretically, and filed it away for future reference. One day I found myself looking at the beginning of this play while free-fencing. In this case it had to do with blade relationships; in the case of the movement of conclusion, it had to do with the relationship of bodies in space. In both cases, the fight presented something to me visually, a relationship of objects in space. This triggered a recollection, which in turn allowed me to start a series of movements that mimicked the recollection. It didn’t matter that, in one case, what I recollected was something I’d reconstructed on the basis of a period “playbook”, and in the other, what I recollected was something I’d seen and practiced a few times. As recollections, both were equally present to my mind in the same way. As such, both were equally able to be played out in real time. It’s as if memory (the past) entered the present (the moment in the fight when I saw and recalled something) and allowed me to move to an inexorable (future) outcome. Of course, all of these moments, at the time, succeeded each other in the present moment; they were all successively present moments. The “playback” was governed by something very much akin to a Platonic Idea or Form (the “Play”, the script). By definition, these re-enactments cannot be perfect; every movement of conclusion, for example, will differ from every other one for various reasons, and none may match the Ideal or perfect Form; but, in fencing, if they are effective, that does not matter.

Puck, this may be a bit more of a response than you were expecting, but as a student, I felt it important to get it out there, for whatever it’s worth, since you are an instructor.

Best regards,

Charles

By Charles Blair on October 20, 2009 4:26 am

Hola,

I wasn’t expecting that conclusion with John either but I got caught with my britches down so to speak and executed it from the bind without thinking about it.

I agree that from the conclusion killing or wounding the adversary is optional and I can think of plenty of reasons why you would merely place the point without pushing it home. At the very least, you avoid having to visit a confessional and at the very best you may gain a new student (or students).

I think Beginning, Middle, and End are useful qualitative time constructions as well as the counters that are described more finely Movement-by-Movement.

As pertains to the idea and action moving from past into present, I think that’s the goal of training.

As we train more, I would expect an additional layer of abstraction to develop were the ‘technique’ is pushed towards the back shelf of the mind while the general goal moves forward. This push into abstraction would be similar to my desire to turn left in a car triggering a simultaneous left turn signal with my left hand, a slowing action on the brake with my right foot, and then a gradual spin of the wheel with my right hand. When the action becomes practiced, I don’t articulate any of these discrete pieces mentally but they each occur correctly in sequence.

The same can occur in a sword fight when we feel pressure in the bind and the desire to counterattack occurs. It may lead us to the conclusion or something else equally correct if we have trained well (and we have good judgment) .

~P.

By puck on October 23, 2009 1:10 am