Spanish Fencing Notation Part 3 – Fighting Distance

(8/31/2009)

Other Martial Traditions

In Aikido the term “Ma-ai” refers to the distance (or interval) between two adversaries. Distance in Aikido is set by your adversary’s ability to strike you. If the adversary holds a weapon like a knife, Ma-ai distance is increased to account for the greater range of the threat.

By contrast, in the Italian fencing tradition distance is typically understood as the distance your attack must travel to strike the adversary.

Close Distance or Narrow Measure– Without moving the feet the adversary may be struck by extending the weapon arm.

Correct Distance or Wide Measure– The adversary may be struck with a lunge.

Out of Distance – The adversary cannot be struck without moving forward.

The key difference between the Japanese measure and the Italian one is the emphasis it places on the conflict. The practitioner of Aikido evaluates the distance needed to defend oneself and the Italian evaluates his own ability to strike. Each martial artist will evaluate offensive and defensive measure, but the measure which is codified provides us an indication of the focus of the art.

The Spanish break distance down into two separate categories using both the concepts of defensive distance used in Aikido and offensive distance used in Italian fencing. Like the Aikido practitioner, the first measure of concern to a Spanish fencer will be the defensive distance.

The Measure of Proportion (Defensive Distance or Place)

(En español – Medio de Proporcion )

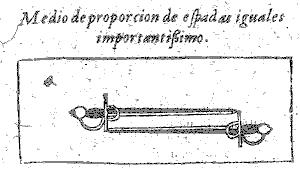

This is the closest distance to the adversary in which you may still effectively observe and react to possible threats. The Measure of Proportion should consider the weapon being used by the adversary and their physical stature. It is very unlikely that two opponents will have exactly the same Measure of Proportion.

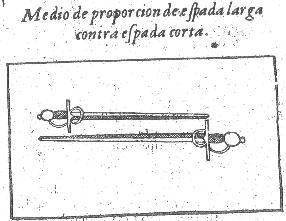

When Pacheco defined the Measure of Proportion he used the relationship between the two weapons as his guide. He advocates setting the distance so that when the adversary extends his arm at full reach, the point of his weapon reaches no further than the cross of your own weapon. If two opponents have equal bodies and equal swords, they will share the same Measure of Proportion.

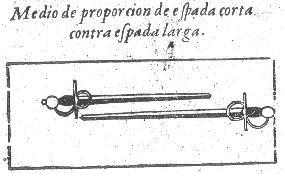

If the opponent has a longer weapon, how you set your own distance should change and your goal becomes to prevent the adversary from closing the distance so that their threat passes the cross of your weapon. The physical size of the adversary is also considered when setting the distance. For example, an opponent with long legs will have a long lunge and the Measure of Proportion will change to compensate.

When your weapon is longer than the adversary’s your goal in setting distance is to close measure enough to maintain your own Measure of Proportion while violating the defensive distance of your adversary and continually keeping them threatened.

Ettenhard, one of Pacheco’s students, later provides a more nuanced description of this distance which is based on a principle rather than setting defensive measure based on the cross of the sword.

| To choose the Measure of Proportion is to determine a proportionate and convenient distance from which the Swordsman can recognize the movements of his opponent, since for whatever determination of his, there should proceed, of body like of arm and Sword: Of body, by means of footwork: and of Sword, by means of the formation of the Technique. |

Restated, the Measure of Proportion must be chosen so that the fencer can recognize a threat from the adversary. You can anticipate the adversary’s actions if you provide yourself enough distance (and therefore time) to recognize motions of the sword or body.

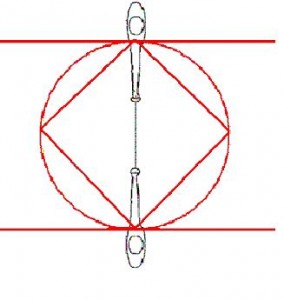

The Measure of Proportion and the Circle

It is important to remember that all the aspects of the Spanish Circle are defined by setting the Measure of Proportion.

The Measure of Proportion defines the Diameter which also defines the Circle, the Square, and the Lines of Infinity.

You should also note that when two adversaries have a different Measure of Proportion, they will have different preferred Diameters and the circle each wishes to create will be defined differently. This indicates again that arbitrarily “walking the circle” isn’t a reflection of the canonical Spanish tradition. Each fencer will attempt to create a more favorable circle which describes the possible footwork and counter-footwork in a fencing action.

As a common practice “walking the circle” would require not only two identical opponents with identical weapons, but also a choreographed plan in which neither fencer took advantage of the shorter distance gained when the adversary steps along the circle (as shown in Part 2). Instead the opponent would need to continually step away from the adversary to artificially preserve the ideal distance in the circle. Walking around a circle while within the striking distance of a non-cooperative adversary would be dangerous.

In order to close distance by stepping along the circle, the action should either control the adversary’s weapon as you move forward or take advantage of a Movement provided by the adversary (such as the thrust into the diagonal reverse shown in Part 1).

The Proportionate Measure (Offensive Distance or Place)

(En español – Medio Proporcionado )

This is the distance that must be covered to deliver a specific attack. For example the Proportionate Measure of thrusts will be different when using a pike, a sword, and a dagger. By using some of Euclid’s work we can provide a demonstration of which attack and position of the arm has the greatest reach.

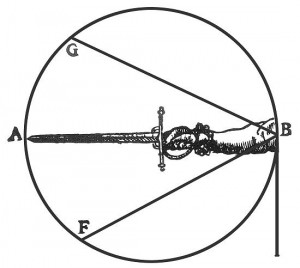

The Right Angle

Carranza demonstrates here that the Line from B to A has the greatest reach. This line is called the Right Angle and provides us with effective offense, counteroffense, and defense.

If the blade is lifted from the Right Angle, as shown in the line from B to G, we have entered the Obtuse Angle and our reach has decreased.

If the blade is lowered from the Right Angle, as shown in the line from B to F, we have entered the Acute Angle and our reach has decreased again.

The thrust typically has the most reach and will have the most favorable Proportionate Measure. In order to reach the correct distance to execute the thrust you may need to gain control of the adversary’s weapon and step along the Square (Transverse Step) or along the Circle (Curved Step). If the adversary prepares a cut, you can strike with a thrust into his preparation and then quickly retreat. By fencing with an extended arm, the Spanish fencer enjoys an advantage in the number of Movements (and therefore Time) when working against an adversary that cuts.

The Spanish cuts (both full circular cuts and the half cuts) are usually actions that occur when the blade has already moved from the Diameter because of a defensive action or because the adversary has deviated your weapon. These typically have less reach than a thrust but correctly executed can be very powerful. Ettenhard indicates that cuts to the head are more common and that horizontal cuts to the body are dangerous and unusual in practice. Because the Proportionate Measure of a cut is larger than that of a thrust, you should never use the cut as your initial action. The greater number of Movements in the cut expose you to counterattack by the thrust. (Remember that an advantage in the count of Movements is also an advantage in Time.)

The Disarm (Movement of Conclusion) requires you to be close enough to seize the adversary’s hilt with your left hand. This typically requires passing forward with your rear foot and the distance you must travel to successfully execute a disarm can actually carry you to the opponent’s Line of Infinity. Because the Proportionate Measure is greater for the disarm, there is a greater degree of danger involved for a fencer executing the disarm.

Final Notes

Remembering the Terms – The two terms Measure of Proportion (Defensive Distance) and Proportionate Measure (Offensive Distance) can easily be confused. At the risk of being slightly silly, I offer the following mnemonic to help remember the difference between the two.

“When asked of his defense, the aggressive fencer ate his opponent.”

- You can remember defensive measure because it has an ‘of’ in the term – Measure of Proportion

- You can remember offensive measure because it has an ‘ate’ in the term – Proportionate Measure

Angle as Position – The angle of the weapon (Acute, Right, or Obtuse) is a common way of describing the position of the weapon in space. You will see the same anglular terms used to describe position in Destreza texts for different weapons, such as the single sword and even Montante.

This is all really fantastic stuff, Puck. How might you describe the movement of a practitioner of the Art in real time. I ask because your conclusions about walking the circle answer a lot of doubts I’ve had for a while. Retreat, advance, step offline? It reads to me as if the spanish fight, from a bystanders view, might look very similar to an Italian, minus the stance. Also, have you discovered anything approximating Constraint in the Spanish school?

By Mateo on September 1, 2009 3:24 pm

Hola Mateo,

I would describe them as ‘backward’, ‘forward’, and ‘transversal’, or ‘curved’ depending on the depth of the offline step. I would say the Spanish fight would look like similar to an Italian sidesword or early rapier tradition.

I’ve got at least one more article I need to write before I can notate an entire action and the counters, but when I get there hopefully this will answer your question better.

The Spanish have ‘Atajo’ which subjects the adversary’s blade from above, but it is part of the Art and not necessarily the Science. If the Science is the method of describing and understanding swordplay that can be applied to any fencing, the Art would be the specific Spanish implementation of the tradition. I want to spend a bit more time describing Science and Notation before I start talking about tradition-specific material like the Atajo.

I will get to the tradition, but I need to give my reader the tools to understand the jargon.

~P.

By puck on September 1, 2009 3:49 pm

In the larger scheme of things, the following comment is relatively insignificant, but I think I’d want to be a bit careful in going from a description of the concept of ma-ai in Aikido to a general (read: blanket) statement about “Japanese measure”–my understanding of ma-ai from kendo includes offensive measure. See, for example, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maai . In kenjutsu, a traditional “guard” involves obscuring the length of one’s weapon from the opponent, and in so doing concealing one’s own effective ma-ai, and in jodo this tactic exists as well (obscuring the length of one’s weapon).

By Charles Blair on September 2, 2009 2:01 am

Nice work, Puck!

But I have to note a little mistake (that is, IMO, of course):

“You should also note that when two adversaries have a different Measure of Proportion, they will have different preferred Diameters and their imaginary circles will be defined differently.”

The problem is that the common circle don’t change depending of the length of a fencer’s measure of proportion, but with the actual distance between the oponents. The circle that changes depending on the length of a given fencer’s measure of proportion is the (surprise, surprise!) the “circle of the measures of proportion”, also called “orbe máximo” (¿maximum orb?), that is centered on the fencer’s centre and it’s radius is the distance from the fencer to the opponent when the fencer is in his measure of proportion.

The common circle can be described as, whatever the relative position of the fencers in a given moment, the line that links both fencers is the diameter of the common circle. Thus, it can be said that there is not “walking the circle” as you’ll never walk more than a step by the same circle.

Also, there are some other circles, concentric and smaller to the circle of the measures of proportion, that show the distances of each proporcionate measure, that are called circles of the proporcionate measures.

By the way, simplifying the measure of proportion and the proporcionate measures as distances, instead of digging a bit in the way of showing them as a combination of distante and relative position from the opponent, may sound like a fine starter, but can be misleading at the end (even the translation of “medio” as “measure” doesn’t fit exactly, you know, but… dammed if I know a better way) Anyway, it’s not easy with Destreza trying to write a “simple, begginer’s guide”: if you simplify too much, “mistakes” like that one appears; but if you put in all that is needed to keep it true and coherent, it cease to be simple in a dammed blink of an eye.

Anyway, I hope my notes will help you to improve your already outstanding work. And, of course, if you need some help or just to get into one of those ” civil and critical discussion of the system ” you speak of at Swordforum, I’m at your service.

Give my regards to Mary

P.D. Well, rereading again the article, I bet that both “mistakes” I speak of are deliberate simplifications. But still I think that they are a little too much.

By Miguel Palacio on September 9, 2009 11:05 am

Hola Miguel,

Good to see you! I’m literally heading to the airport this morning so I can’t discuss much until next Tuesday, but I’m glad to see you’re looking over the articles and providing feedback. I think the discussion can improve the presentation and that’s the ultimate goal.

~P.

By puck on September 9, 2009 5:38 pm

Hola Miguel,

Thanks for the notes on this and I agree with your feedback for the most part which makes it clearer. It isn’t that there are two Major Circles (common circles) but rather each diestro has a different goal when setting the distance and wants to create a common circle that provides an advantage in distance.

It is the non-cooperative nature of the adversary that makes stepping forward in distance so dangerous. If only I could convince my adversaries to let me do whatever I like!

;-D

I have also added an alternative synonyms for Medio de Proporcion (defensive distance or place) and Medio Proporcionado (Offensive distance or place).

Mary says ‘hola’ back and please keep up the feedback.

~P.

By puck on September 17, 2009 4:46 pm

(9/17/2009)

EDITS —

Changed this:

“You should also note that when two adversaries have a different Measure of Proportion, they will have different preferred Diameters and their imaginary circles will be defined differently. This indicates again that arbitrarily “walking the circle” isn’t a reflection of the canonical Spanish tradition. Each fencer will act with their own unique instance of the circle which describes the possible footwork and counter-footwork in a fencing action. ”

To this:

“You should also note that when two adversaries have a different Measure of Proportion, they will have different preferred Diameters and the circle each wishes to create will be defined differently. This indicates again that arbitrarily “walking the circle” isn’t a reflection of the canonical Spanish tradition. Each fencer will attempt to create a more favorable circle which describes the possible footwork and counter-footwork in a fencing action.”

Added additional synonyms:

Medio de Proporcion (Defensive distance or place)

Medio Proporcionado (Offensive distance or place).

By puck on September 17, 2009 4:51 pm

ok,again.you can complete this link with te termin “medio proporcional”.mentioned at LORENZ DE RADA ,WORKS,IF YOU HAVE NO IT’S ,ASK ME FOR THEM.IESUVINCIT

By IESUVINCIT on October 14, 2009 10:54 am

[…] LINK TO ARTICLE 3 […]

By Spanish Fencing Notation Part 5 - Strength of the Weapon | A Midsummer Night’s Blog on November 3, 2009 7:01 pm